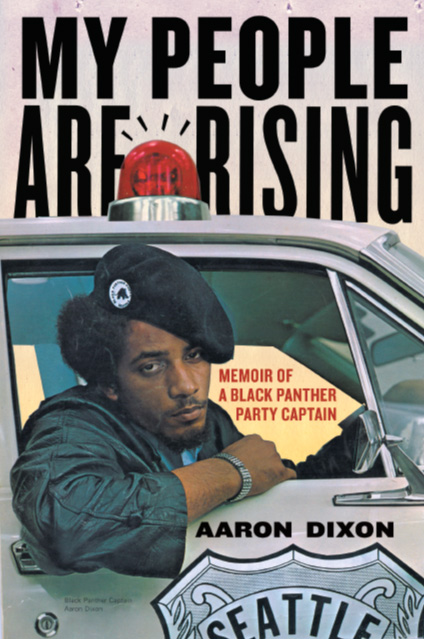

Former Black Panther Aaron Dixon speaks at PCC Cascade about his experience with and the history of the Black Panthers. Photo by Pete Shaw.

Story by Pete Shaw

There are few groups in the annals of US history more willfully misunderstood than the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. According to the FBI line pushed by the corporate media, the Black Panthers became the face of everything white people should fear: black men with guns. The Panthers hold a place in American consciousness that has almost nothing to do with reality and everything to do with image: Leather jackets, black berets and guns – always guns. Their very existence came to represent a threat to the stability of the country.

To be fair, much of the Black Panther agenda was a threat to the stability of the US ruling class. But this had nothing to do with weapons. Henry Kissinger, when talking about the election in Chile that brought Salvador Allende to the presidency, said Chile was a virus that if not destroyed would send the wrong message to the rest of South and Central America about the possibilities for social and economic change. Similarly, the Black Panthers were, at least according to President Richard Nixon and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, a virus that also needed annihilation. Part of this destruction was to craft a narrative that willfully obscured the truth about the Panthers.

Seeking to remedy this omission, Aaron Dixon, who at 19 years old was a co-founder of the Black Panthers in Seattle, has written a book, My People Are Rising: Memoir of a Black Panther Party Captain (Haymarket Books, 2012). Dixon spoke at PCC Cascade in February about his experience with and the history of the Panthers.

“My generation was the one that had the privilege of watching the Civil Rights Movement unfold,” Dixon told his audience. Like hundreds of thousands of young black people in the US, Dixon and his elders – elders whom Dixon said were revered – watched Martin Luther King demand equal justice, saw the news of the 1963 bombing of the Birmingham Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and watched the Watts Riots of 1965. He witnessed countless black people standing up to demand their place at the table, and he saw leaders of that movement murdered. Dixon mentioned the profound effect of the murders of President John F. Kennedy, Medger Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King.

These events, along with the day to day living conditions that they punctuated, pushed Huey Newton and Bobby Seale to form the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, California, in 1967. There, as in many parts of the country, police violence against black people was vicious and rampant, and Newton and Seale set out to do something about it. They formed neighborhood defense committees and followed police while carrying loaded weapons – legal in California until outlawed by the Mulford Act of 1967 – to protect black people from police injustice.They also demanded an end to all forms of oppression of Black people.

In 1968 Dixon helped found the first black student union at the University of Washington, and on April 4th he was arrested for unlawful assembly during a sit-in at Franklin High School. The sit-in revolved around a fight in the school hallway involving two black students and one white student. The black students were reprimanded and the white student was not. While Dixon was in jail that day, he heard that Martin Luther King had been murdered. “I thought to myself, ‘The picket sign is going to be replaced by the gun.’”

As Dixon put it, the piling on of injustices led more and more black people to stop fearing their oppressors, and people like Newton and Seale were at that visible leading edge.“He wasn’t afraid of anyone or anything,” said Dixon of Newton. He was also brilliant, and in Newton and the other Black Panthers, Dixon saw what needed to be done in Seattle.

Two days after King’s assassination, Black Panther Party first recruit and treasurer Bobby Hutton was gunned down by the Oakland police who had trapped Hutton and fellow Panther Eldridge Cleaver in a West Oakland house after a shootout. According to Cleaver, Hutton had surrendered when the police shot him with over a dozen bullets.

Dixon attended Hutton’s funeral and soon told Seale he wanted to form a Seattle branch. Seale said he would need two weapons and 2,000 rounds of ammunition for each Panther, as well as a rigorous education program. Dixon was one of many drawn to the program of the Black Panthers, and soon the Panthers had branches in nearly every state.

The Panthers began to shift their focus from self-defense of the black community to broad coalition-building that Dixon described as “an international struggle against capitalism, imperialism, and oppression.” They also developed Survival Programs that provided for the needs of the poor within their communities. The most famous of these was the Free Breakfast for Children program – which Dixon helped start – that eventually appeared in every major US city with a Black Panther chapter. The impetus for the program, noted Dixon, was, “How can Johnny learn 5 apples plus 3 apples equals 8 apples when he doesn’t have an apple?” The program was so successful that the federal government was compelled to adopt a similar one in schools.

The Black Panthers also opened medical clinics, with the first NW clinic in Seattle, and other services such as free ambulances, pest control, and legal aid. “Wherever there was a need within the community,” said Dixon, “we developed a program around it.”

Dixon also told stories about his time spent in Oakland – the kind of stories historians spend years mining – the stuff that puts the humanity to the life. One memorable tale included a night of partying with the Oakland Panthers when suddenly a shot rang out upstairs. The group ran up to find a Panther holding a gun in front of a television screen blasted to pieces. The shooter had been watching a cowboy and Indian movie and finally decided it was time the Indians won.

Less humorous was Dixon’s “baptism,” that occurred a several weeks after Hutton’s death when Dixon and a few Panthers found themselves face to face with a group of 20 to 25 police. Dixon was terrified there was going to be a shootout. Fortunately nothing happened.

While armed black men certainly sounded an alarm throughout some portions of the country, it was only when the Panthers started reaching out beyond Black neighborhoods to all poor people and coordinating their Survival Programs that they became a virus. J. Edgar Hoover declared the Black Panther Party “the greatest threat to the internal security” of the country and pledged to wipe it out by 1970. Black Panther leaders John Huggins and Butchy Carter were murdered at UCLA by assassins who likely had connections with the FBI , and across the country police or the FBI raided Black Panther Party offices. Numerous Panthers were jailed; some remain in prison to this day.

This program of extermination culminated with the assassination of Chicago Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton. Hampton’s murder was orchestrated by the FBI and the Illinois state police. Dixon believed Hampton was the next great black leader, one who combined the righteousness of Martin Luther King with the directness of Malcolm X. Perhaps Hoover feared that Hampton was the “Black Messiah” that would unify the black masses, as was later revealed in the Church Committee’s investigation of the FBI’s Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO), also used to disrupt and destroy other social movements. Dixon called Hampton’s assassination the “saddest day in my life,” and said it left a huge, irreplaceable hole within the Black Panther Party.

As an official organization, the Black Panthers have come and gone, but like their breakfast program, Dixon has endured. In 2002, he founded a non-profit organization to provide transitional housing for homeless young adults. Not surprisingly, Dixon also focuses on teaching youth the importance of serving the community. In 2006 he ran for Senator in Washington on the Green Party ticket, seeking immediate withdrawal from Iraq and supporting a single payer health care system.

What is the legacy of the Black Panthers? As with all questions of history, there are no simple answers. The Survival Programs seem easy enough to defend and deserve continuation and expansion. These programs, however, are often ignored by a dominant narrative intolerant of viruses. During the late 1960s, the Black Panthers were often compared with the Ku Klux Klan, and today’s Tea Party has been looked at alongside the Black Panthers.

These equivalencies are false and should be rejected. The purpose of the Black Panther Party was to extend justice to people to whom it long had been denied. They were seeking to expand what the textbooks call the blessings of liberty, often against the power of the state. The Ku Klux Klan and the Tea Party stand in opposition to this: they and similar groups have always sought to limit freedom to themselves, to white people – often of particular race, gender, sexuality, and creed – and they have often enjoyed the support of the state. In the case of the Klan and others of their ilk, the violence they inflicted upon those they sought to oppress was far greater than any acts committed by the Black Panthers.

Earlier in the day Dixon appeared on KBOO’s Voices From the Edge hosted by Jo Ann Hardesty. During the hour-long segment, Hardesty asked Dixon some question about what has guided him in his life. “When you come into the world, everyone has a role in this life,” Dixon said. That role is making sure our world, our nation, and our society is better.”

It’s a fair enough assessment, if not one so easily assessed. Dixon’s life has been one of struggling for a better place, and while he lacks the “star power” of better known people who have followed Martin Luther King’s arc of history toward justice, it is his lack of aura that makes a better future seem more tangible. The steps he has taken toward that better world, nation, and society are greatly admirable. That he continues pressing forward is even more so.