Story and photos by Pete Shaw

When I was growing up, I knew my neighborhood’s mail carrier. He is in some of my earliest memories. He was portly, with a closely cropped beard, and in the Winter he sometimes wore a thick hat with ear flaps. My mother talked often with him, and during the Winter holidays she tipped him. He came about the same time every day, first in his US Postal Service jeep, and later in his USPS truck. When I was in college, he was still the neighborhood mailman. And his choice of Winter headgear never faltered.

Every place I have lived, I’ve known my mail carrier. When I first moved to these parts, across the river in Vancouver, our mail carrier gave me tips on neat places to visit, as well as on how to prune a tree that reached out over the street and threatened to scratch his truck. And for years in North Portland, I have known my mail carrier. Scott, who liked fishing and the chocolate chip cookies I would bring back from New Jersey, retired a few years ago. Maleté replaced him, and after a few years and a knee injury that led to a position requiring less walking, gave way to Jeremy taking up the route. Every day around 2:30 in the afternoon, they came. Their once a week substitutes were rarely far off the pace. And even if all they delivered was bills, I enjoyed seeing them.

But in early Autumn of last year, the mail began coming late. I would not mind if it was two hours late, although it would be nice if it was predictably so. But for the first time in my life, I had to put out a note reminding myself to turn on the porch lamp as the late afternoon sun waned so the mail carrier could see where they were going. Or rather, so the carriers–plural–could see where they were going. I did not and still do not know many of them, and more importantly and disappointingly, because their delivery times are not predictable and there are quite a few of them, I am not confident I will ever get to know any of my mail carriers. Mail deliveries have become hollow business formalities rather than meaningful and nourishing neighborhood relationships.

I assumed this disorder was just the way of things. People retire. People move. People find other interests. It takes time to break new people in, for them to get used to their routes and routines, to make those various connections with postal customers regarding forwarded mail, needed signatures, and eventually, the small–and sometimes deeper–talk that makes any relationship worthwhile.

It turns out, however, that this is not simply a predictable disruption of my mail service. And it is not the case for any and all mail that arrives to and is delivered from the Kenton Post Office in Portland, Oregon, 97217. Without notifying affected customers, in September 2019 the United States Postal Service (USPS) unfurled a pilot project known as “consolidated casing” which separates mail sorting from delivery. The experiment is being conducted at 64 other post offices around the country, with the residents of 97217 being the only ones in Oregon subjected to this incoherent and, by any rational standard, inefficient venture.

Consolidated casing was supposed to make for more efficient delivery. But at a forum at Celebration Tabernacle Church in downtown Kenton, just down the block from the post office, about a 100 people gathered on Saturday morning, January 26, to describe for Representative Earl Blumenauer a pattern of late and erratic deliveries, mis-delivered mail, and a changing cast of carriers who looked exhausted from the mental and physical strains of consolidated casing. Retired letter carrier and organizer for Communities and Postal Workers United Jamie Partridge observed, “We have not done well.”

Here’s how things have more or less worked for the past few hundred years, according to Willie Groshell, president of the Oregon State Association of Letter Carriers. Groshell described a normal day for the letter carriers at the 31,259 Postal Service-managed retail post offices in the US whose customers are not being used as consolidated casing guinea pigs: show up, clock in, check your vehicle, go to your individual case for your route, get the mail ready, get it down in route order, load up your truck with mail and packages, do your route, and at the end of your day return to the post office.

Groshell summed it, “One route, one person, managed by the same person from the start to the end. That’s how it is everywhere else in the entire state of Oregon.”

The detrimental effects of consolidated casing are being felt throughout the 97217 community. Rachel Browning, who with her brother Preston owns Salvage Works in downtown Kenton, described some of the difficulties consolidated casing has brought to her and her business. Salvage Works employs 13 people, which Browning emphasized means “13 families with kids,” and when, as she described a recent experience, “a $14,000 check is held up for five days, I can’t make payroll.” In other words, 13 people go home to their families without their expected paychecks.

One might counter Browning by noting that a substantial amount of commerce is now conducted online. While this is true, that arguable convenience comes with a cost, namely what Browning described as a surcharge of “up to 3 percent.” So Browning for her part thinks “receiving a check in the mail is awesome.”

Preferably, your mail. Cameron Taylor, who is the business agent for the Bakery and Confectionary Workers Union, Local 364 on North Lombard Street, a six block jaunt from the post office, described having an $11,000 check go missing for three weeks. The union’s mailbox is among many in a bank of mailboxes, and the check had been placed in the wrong one. Taylor also noted that mail pickup and delivery was inconsistent.

Browning’s assessment echoed that of the Kenton Business Association (KBA), of which she is a board member. In a letter to the USPS from the KBA that she read aloud, the group announced that they had “seen a drastic shift in the reliability of our mail service.” The letter touched on what became common refrains throughout the meeting: deliveries occurring before businesses opened or after they closed, piled up orders that were not picked up for days, no prior notice from the USPS regarding the change in service, and carriers being unduly burdened with unfamiliar and long routes.

“This entire experience,” said the KBA, “has been a huge frustration for us, and to see it happen at the expense of our dedicated and hardworking carriers is an extreme disappointment.” Other associations including the Arbor Lodge and Humboldt neighborhood associations weighed in with similar complaints.

Blumenauer gave the audience his personal history with the post office. His parents worked for the post office “and made a fine middle class living for themselves and their children.” He also noted how even more importantly, he saw his parents’ “depth of affection for the customers they served.” Waxing in his folksy way, Blumenauer told of how when his father was delivering mail around the Winter holidays, “he almost needed a special protective belt because he got so many presents. Bottles of something and cookies.” This homespun memory led to why Blumenauer has been at the forefront of standing up for the US post office, its carriers, and the communities they serve. His father, like many letter carriers, “was dedicated to what he did, and he had a connection with those customers and that community…And I guess I admired that.”

That feeling of communal connection is hardly unique to Blumenauer. Alicia Richards, who has lived for nearly 25 years in the Overlook neighborhood, once had my former carrier Maleté as her postman. She described a person who sounded completely familiar to me, both personally and historically. Aside from delivering the mail on time and knowing where to place packages when she was not home, Alicia described Maleté as “a personal part of our village” recalling an ironic moment when he helped a neighbor find their lost dog.

Overlook resident Peter Parks talked about the great care his mail carrier had shown his nonagenarian neighbor. Parks described the once on-time deliveries–3:30, give or take ten minutes–that his neighbor came to expect. Likewise, the mail carrier anticipated seeing her. When they did not, they checked in on her.

Now Richards, like Parks, says she does not know her mail carrier, or rather, her mail carriers, whose erratic deliveries sometimes arrive as late as 10 PM.

Richards, like others who spoke, told how they don’t have the time to know their carrier because the carrier simply does not have enough time and because each day might bring a new carrier. And this also has an effect on those carriers.

“The diminishment of the quality of life,” said Richards, “of these workers is a really important thing that we should be thinking about because I think in our economy, quality of life and making sure we have the things to take care of our families is a really important part of job satisfaction.”

Colin Moore, who until a week ago was a mail carrier stationed at the Kenton post office, described his job prior to consolidated casing in terms that would be familiar to a gardener. “You tend to your route,” he said. “You care for your route. I used to have a route where I came in and I cased the mail and I tended to the route. You tend to the forwards. You tend to the vacation holds. You take care of that route.”

But for Kenton residents and residents of the other 64 US zip codes upon whom consolidated casing is being tested, their mail is no longer tended to by their carrier, and their carrier is not the same person day after day.

Moore described a mail carrier’s job under consolidated casing as decoupled, and indeed he described the tending to the mail before delivery as now being done by a few skilled people who arrive in the morning to take care of the work. They do not interact with the people to whom the mail is delivered. They do not know their needs when it comes to delivering packages. Their relationship with postal customers is solely transactional.

Carriers, Moore said, now show up at 9:30 AM and get out on the street. Prior to leaving his mail carrier job in Kenton, Moore said consolidated casing had resulted in him getting a route that he described as 15 to 16 miles of “walking all day.” His day officially ended at 6:30 PM. From people’s testimony on Saturday morning, it was clear that Kenton post office mail carriers are putting in significantly longer hours.

Blumenauer, who earlier had mentioned the postal service’s role in establishing the middle class, also had his mind on what has for many years been a war on the post office. That fight dates back to the Nixon Administration, but it took a new and sinister turn in 2006 when Congress passed and President George W. Bush signed the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act (PAEA). That watershed legislation forced the Postal Service to prefund the healthcare benefits for all current and projected employees for the next 75 years. It was unprecedented, and no other government agency was so burdened. Furthermore, it is impossible to imagine the same requirement becoming a federal law that all corporations doing business in the US must obey. It would destroy the vast majority of them within a matter of hours.

So it should come as no surprise that the postal service has fallen on hard times. Between fiscal years 2007 and 2017, the PAEA forced the USPS to set aside about 10 percent–between $5.4 and $5.8 billion–of its annual budget for the health insurance mandate, much of that money going to prefund retiree health insurance benefits for employees who had yet to be born. But beginning in fiscal year 2012, the USPS defaulted on these required payments.

A February 16, 2015 USPS Inspector General blog post compared the onerous and unheard of burden imposed upon the USPS by the PAEA to a credit card company telling its customers, “You will charge a million dollars on your credit card during your life; please enclose the million dollars in your next bill payment. It’s the responsible thing to do.” The post noted that by 2015 the Postal Service had set aside “more than $335 billion for its pensions and retiree healthcare, exceeding 83 percent of estimated future payouts. Its pension plans are nearly completely funded and its retiree healthcare liability is 50 percent funded–much better than the rest of the federal government.” The Inspector General also wrote, “The Postal Service’s $15 billion debt is a direct result of the mandate that it must pay about $5.6 billion a year for 10 years to prefund the retiree healthcare plan.”

And a May 2017 report issued by the USPS Inspector General stated that of the $62.4 billion the Postal Service lost from 2007 to 2016, $54.8 billion was due to “prefunding retiree health care.”

This has downstream effects as well. The Inspector General’s 2015 blog post stated the prefunding mandate “has deprived the Postal Service of the opportunity to invest in capital projects and research and development.” The May 2017 report noted that because of its debt, which is primarily due to the mandate, the Postal Service now has “an inability to borrow.” In material terms, this means the USPS cannot borrow money which could be used to renovate and upgrade existing post offices, as well as build new ones. Or to update the vast fleet of vehicles used by postal service workers. Never mind taking on other ideas, some embraced by Blumenauer, including reviving a postal savings bank, having post offices off computer services similar to those available at libraries, and using mail carriers to help count people for the census.

Julius Fildes, a mail carrier who calls 97217 home but delivers elsewhere, places the blame squarely on the PAEA and the Postal Service, describing the latter as “a bottomless wellspring of bad ideas” and citing its refusal “to acknowledge that this bad idea of theirs has been an abject failure.” Moore had earlier noted a wide array of PAEA-induced failures by the USPS, but noted that in a presentation before the House Oversight Reform Committee in April, 2019, Postmaster General Megan Brennan celebrated the success of the agency she oversees at pursuing “an aggressive agenda to cut costs.”

Brennan is hardly the first Postmaster General to pursue cuts, particularly since the PAEA was made law. But she is continuing a series of cutbacks that took off with its passage and among other things has seen cuts of over 200,000 postal employee jobs and an increase in part-time positions. As Fields said, “It (the PAEA) was intended to create a financial crisis within the postal service, and it has succeeded.”

That should come as no surprise. It has long been a project of capitalists to privatize the USPS, and presidents and politicians dating back to the Nixon Administration have had the Postal Service in their sights. Impose undue hardships upon it, make cuts to try and balance those hardships, and keep that cycle going until one day you can blame the bloated and out of control institution that you forced to become bloated and out of control for its woes, and then in the final act, privatize it and sell it off at rock bottom prices.

For Taylor, consolidated casing fit the mold. “Honestly,” he told Blumenauer, “I don’t understand why this experiment is continuing. The only thing I can think is that the Postal Service wants to generate enough complaints to justify privatization.”

People like their postal service, and when they see it being attacked, they fight back, and they do so creatively. Earlier, Moore had mentioned the GPS tracking device that mail carriers wear while doing their deliveries and pickups. Kenton resident Susan Alberg wanted to examine mail carriers’ GPS data so people could compare the data from before and during the experiment with case consolidation would confirm the anecdotal evidence that has been piling up among the residents of 97217 since September, that delivery had become less reliable and less efficient. Moore added that the GPS data would also show that quite a few carriers work through their lunch, losing a half hour of pay while working off the clock.

Blumenauer said he appreciated the idea and suggested a Freedom of Information request would be in order.

Ann Howell, the Communications Chair for the Bridgeton Neighborhood Association, said she had not heard of the change at her Kenton post office, something that, because of her position, embarrassed her. But she assured the audience that she would be bringing word to her Hayden Island neighbors, as would people hailing from the Piedmont neighborhood.

Fildes talked about legislation sitting before Congress that would help get the Postal Service back on its proper footing. House Resolution 2382 (the USPS Fairness Act), he said, had enough co-sponsors from both parties, including Blumenauer, to require a vote. On Thursday February 7, the House passed the bill, which would get rid of the prefunding requirement of the PAEA.

There is a companion bill in the Senate, SR 2965. Fildes urged people to push Senators Merkley and Wyden to support the Senate version.

Blumenauer seemed to genuinely enjoy being around constituents willing to fight with him. “This is, I think, an example of steamrolling,” he said, “thinking that this is an area that, well, they can experiment.” And then, lifting his tone with near palpable sarcasm, continued, “People aren’t going to, maybe, notice? Or they won’t push back? And I can’t tell you how much I appreciate you being here this morning to help me push back.”

Blumenauer visits often, and the USPS–the one that he remembers from watching his father–apparently means a lot to him. But he works far from North Portland, and the Kenton mail carriers don’t make the trek to Washington, DC, 20515.

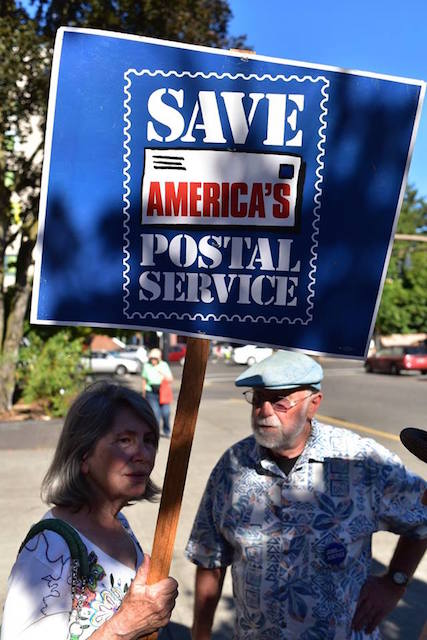

So resistance begins here, in 97217.