by Eric Iseman

“If ye love wealth greater than liberty, the tranquility of servitude greater than the animating contest for freedom, go home from us in peace. We seek not your counsel, nor your arms. Crouch down and lick the hand that feeds you. May your chains set lightly upon you, and may posterity forget that ye were our countrymen.”

–Samuel Adams

Editor’s Note: Governments rise and fall. History lumbers forward. Or does it? Even a casual examination of the past reveals the similarities between different eras, reminding us that human evolution is a slow curve, which seems, at times, as if it is winding back on itself. Witness the early foot soldiers of the American Revolution–The Sons of Liberty–a crew whose similarities to today’s Occupiers are well worth noting.

The Sons of Liberty are best known for undertaking the Boston Tea Party in 1773, which led to the American Revolutionary War in 1775. The Sons, a small group of workers and tradesmen, originated in Boston in 1765. By the end of that year, the Sons of Liberty existed in every colony. Though each colony had its own constitution, they vowed to fight together for freedom. In New York, as stated in their “Constitution of the Sons of Liberty of Albany,” they refused to back down, promising, “As in our present distressed condition…our own fixed and unanimous resolution to persevere to the last in the vindication of our dear bought Rights and Privileges, the very Essentials of our peerless Constitution.”

The origins of the Revolution emanated from the British defeat of France in the French and Indian War. After the war, the British Empire sought to provide offices for hundreds of military officers and 10,000 men, and intended to have the Americans pay for it. The British passed a series of taxes, and when the Americans refused to pay on the argument of “No Taxation without Representation” (there were no American representatives in Parliament), Parliament insisted on its right to rule the colonies. The most incendiary tax was the Stamp Act of 1765, which caused a firestorm of opposition through legislative resolutions (starting in the Province of Virginia), public demonstrations (initiated n the Province of Massachusetts), threats, and occasional hurtful losses.

As noted, 1765 marked the initial formation of secret groups in major American cities. Boston had the “Boston Caucus Club,” led by Samuel Adams and comprising artisans, merchants, tradesmen, and professionals, as well as the “Loyal Nine”.[1] Groups such as these were absorbed into the greater Sons of Liberty organization. In the popular imagination, the Sons of Liberty was a formal underground organization with recognized members and leaders, a unifying name that helped them promote inter-Colonial efforts against Parliament and the Crown’s actions, and a motto: “No taxation without representation.”

After independent starts in several different colonies, the Sons spread month by month. The August 1765 founding in Boston was followed on November 6 by a committee set up in New York to correspond with other colonies. In December an alliance was created between groups in New York and Connecticut. January 1766 bore witness to a correspondence link between Boston and New York City, and by March, Providence had initiated connections with New York, New Hampshire, and Newport, Rhode Island. March also marked the emergence of Sons of Liberty organizations in New Jersey, Maryland, and Norfolk, Virginia, and a local group established in North Carolina was attracting interest in South Carolina and Georgia.

In order to avoid direct connection with any violence that the organization may have initiated, Samuel Adams and his cousin John were not open members of the Sons of Liberty; however, there were recognized Sons with influential power, such as “Benjamin Edes, a printer, and John Gill of the Boston Gazette (who) produced a steady stream of news and opinion.” Samuel Adams was affiliated with the Boston Gazette and published many articles under a pen name, thus implying his participation in the Sons through writing, shared opinion, and association with prominent members. Though these men were speaking out against the actions of the British government, they still claimed to be loyal to the Crown. Their initial goal was to ensure their rights as Englishmen.

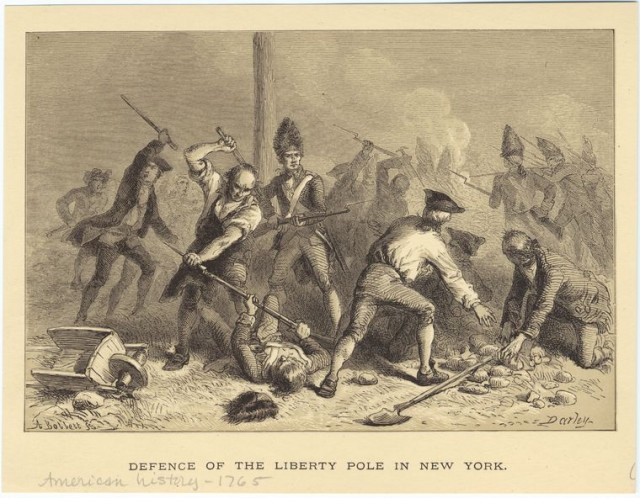

The sons publicized their cause through newspapers, protests, and, most notably, the erection of Liberty Poles. The Poles were symbols of dissent against the British, and when the red-and-white striped flag–known as the rebellious stripes–was raised, it was a call to all Sons and other supporters to meet and discuss their complaints about British rule. The Poles were cut from white pine, in defiance of the public prohibition against this wood, which was reserved exclusively for masts of His Majesty’s navy.

The Poles were so controversial that, when soldiers knocked one down in New York on January 18, 1770, it let to The Battle of Golden HIll, the first major bloodshed between colonists and the British Army. Members of Parliament were actually scared into hiding, as tensions began to build between the Sons and the British, and the Sons displaced the royal government in nearly every colony. When British troops began to fight harder, attempting to reassert control, the Sons began to work together and unite the colonies for the first time.

The inter-communication afforded to the Colonies by the widespread nature of the Sons of Liberty allowed for decisive action against the Townshend Act in 1768. One by one the groups penned agreements limiting trade with Britain and imposing a highly effective boycott against importation and sale of British goods.[13] The British Crown came to refer to the “treasonous” Sons of Liberty as the “Sons of Anarchy”, “Sons of Violence” or the “Sons of Iniquity.”

One of the most popular causes of the Sons was the fight against the Stamp Act imposed by the British Parliament. Office holders identified by the Sons as having taken part in the Stamp Act injustice quickly fell out of favor and lost their positions once local elections were held again. The Sons held meetings to decide which candidates to support, selecting those that would bring about the desired political change.

To add weight to their cause, the Sons knew they needed to appeal to the masses that made up the lower classes. Though the lower classes often agreed with the ideas presented by the Sons of Liberty, they often wanted more action than words and a simple show of numbers. As such, the property of the gentry, customs officers and other British authorities would fall victim to the volatile nature of mobs. Violent outbreaks raged intermittently from 1766 until the Patriots gained control of New York City government in April 1775. In Boston, they burned an effigy of local stamp distributor, Andrew Oliver. When he did not resign, they escalated to burning down his office building. Even after he resigned, they almost destroyed the entire house of his close associate, Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson. It is believed that the Sons of Liberty did this to excite the lower classes and get them actively involved in rebelling against the authorities. Their violent actions made many of the stamp distributors resign in fear.

The Sons were also responsible for the burning of HMS Gaspée in 1772. In December 1773, the Sons of Liberty issued and distributed a declaration in New York City called the “Association of the Sons of Liberty in New York”, which formally stated their opposition to the Tea Act, proclaiming that anyone who assisted in the execution of the act was “an enemy to the liberties of America” and that “whoever shall transgress any of these resolutions, we will not deal with, or employ, or have any connection with him”. The Sons took direct action to enforce their opposition to the Tea Act at the Boston Tea Party. Members of the group, wearing disguises that evoked the appearance of Native American Indians, poured several tons of tea into the Boston Harbor in protest. (The most famous of all tea parties was planned in the long room above Benjamin Edes’ print shop.).

Early in the American Revolution, the Sons of Liberty generally evolved into, or were superseded by, more formal groups such as the Committee of Safety. After the end of the American Revolutionary War, Isaac Sears, along with Marinus Willet and John Lamb, in New York City, revived the Sons of Liberty. In March 1784, they rallied an enormous crowd that called for the expulsion of any remaining Loyalists from the state starting May 1. The Sons of Liberty were able to gain enough seats in the New York assembly elections of December 1784 to have passed a set of punitive laws against Loyalists. In violation of the Treaty of Paris (1783), they called for the confiscation of the property of Loyalists.

In retrospect the ballooning of a small, localized group of patriots into a huge united front for freedom is a truly remarkable feat, demonstrating how a mere pile of revolutionary sand can turn into a freedom fighting beach.

Remarkable members:

• John Adams, lawyer, Massachusetts

• Samuel Adams, political writer, tax collector/fire warden, Boston

• Benedict Arnold, businessman, Norwich

• Benjamin Edes, journalist/publisher Boston Gazette, Boston

• John Hancock, merchant/smuggler/fire warden, Boston

• Patrick Henry, lawyer, Virginia

• John Lamb, trader, New York City

• William Mackay, merchant, Boston

• Alexander McDougall, captain of privateers, New York City

• James Otis, lawyer, Massachusetts

• Paul Revere, silversmith, Boston

• Benjamin Rush, physician, Philadelphia

• Isaac Sears, captain of privateers, New York City

• Haym Solomon, financial broker, New York and Philadelphia

• Charles Thomson, tutor/secretary, Kentucky

• Joseph Warren, doctor/soldier, Boston

• Thomas Young, doctor, Boston

• Marinus Willett, cabinetmaker/soldier, New York

• Oliver Wolcott, lawyer, Connecticut

Notable Quotes:

“We must all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately.”

— Benjamin Franklin, at the signing of the Declaration of Independence

“… God forbid we should ever be twenty years without such a rebellion. The people cannot be all, and always, well informed. The part which is wrong will be discontented, in proportion to the importance of the facts they misconceive. If they remain quiet under such misconceptions, it is lethargy, the forerunner of death to the public liberty…. And what country can preserve its liberties, if its rulers are not warned from time to time, that this people preserve the spirit of resistance? Let them take arms. The remedy is to set them right as to the facts, pardon and pacify them. What signify a few lives lost in a century or two? The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time, with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure.”

–Thomas Jefferson

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

–Preamble to the U.S. Constitution, May 1787