1929

Between the sphinx and the bank vault, there is a taut

thread

that pierces the heart of all poor children

–cried Federico Garcia Lorca after visiting Wall Street in 1929. His vision sharpened by gathering storms of fascism, in his native Spain and across the European continent, compounded by new forms of corporate control in the US, and a broken heart over unrequited love, he poured his soul into the powerful “Poet in New York” poems. Visiting Wall Street, the sidewalks barely swept of fall leaves and the remains of leaping bodies–small-time investors convinced that untold wealth shall be theirs only to see life-savings vanish, and of the occasional banker who followed their lead–his eyes pierced Capitalism’s many veils.

Wall Street, built on Iroquois and Algonquin land, was named for the wall that the Dutch colonists erected to keep the English and the Indians away. Soon, the Dutch West Indies Company, early and major importer of slaves, brought them to New Amsterdam, too. Auctions in human flesh were held nearby, a connection deepened by major banks and investment firms turning money from slave transactions to new gold and influence. Later, a place giving birth to economic shenanigans and scams, crises and broken dreams–vast fortunes for the few, misery for the many.

October 2011

It is now fall 2011. Eight decades have passed since the Andalusian poet and play-writer created his eulogy. Today the center of global finance is inhabited not only by those Lorca depicted as the ones “who drink a dead girl’s tears at the bank or eat pyramids of dawn on tiny street corners,” but also by thousands of protestors, joined by thousands more across the land. They were not invited to the feast, but here they are, here we are. In Portland, Oregon, a few hundred are camping in Chapman and Lownsdale Parks, across from City Hall and from the jail, (known as “The Justice Center.”)

The parks are named for William Williams Chapman and Daniel H. Lownsdale, politicians and businessmen of Portland’s early days, who fought in the 1850s Rogue River wars, helping to drive out the local tribes and secure the land for gold prospectors, cattlemen, railroad barons and waves of newcomers. An obelisk and fountain are dedicated to the soldiers of the Second Oregon U.S. Volunteer Infantry killed in the Spanish-American War, an imperial adventure that resulted in the conquest of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, and the death of hundreds of thousands of civilians and fighters resisting the invaders. Near the monument is “The Promised Land” sculpture, commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Oregon Trail. Its bronze pioneer family — father, mother, and son holding a Bible — have been decorated with a papier-mâché longhorn skull and a “Save Our Oregon” cardboard sign by protestors. The parks testify to the long history of conquest, deceit, and suffering inflicted, and of the immensity of the task ahead.

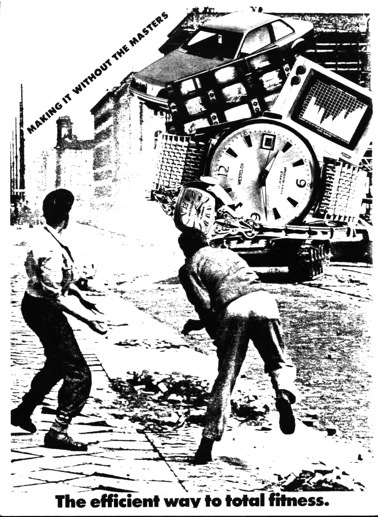

Every day there are classes, discussions, committee meetings, marches, and a General Assembly attended by hundreds. Two months ago, I marched with 30 souls; Four weeks later, snaking through the center of town, we numbered in the thousands. Portland’s movement is comprised of people of different backgrounds, ideas, and levels of faith in what is desirable and possible. Some maintain that Portland is a liberal and humane city and trust the mayor and the police, while others point to the historical role of the police in Portland in suppressing dissent and maintaining the status quo, and the arrest of 25 occupiers, trying to establish a new encampment, by horse-mounted police and dozens of cops in full riot gear- and to a long history of racism and economic inequality. There are those who believe that the system is repairable and worth saving, and are willing to settle for legal constraints on corporate power, or for social services, like universal health care, available in all modern societies, while others want a radical change in the way society is organized and how we live. In the community forums and informal gatherings discussions on short-term successes versus the long haul, being “realistic” versus dreaming, take place. There is, however, general agreement about the importance of consensus-building and democratic decision-making and the necessity of creating models of living that differ from those of hierarchical and class society.

December 2011

On Saturday night, November 13th, at midnight, the forty-eight hour ultimatum to evacuate the camp, announced by Sam Adams, Portland’s young and liberal-sounding mayor, arrives. Speaking of “health and safety concerns, “ he bowed to the dictates of the Portland Business Alliance, and after a conference call with seventeen other mayors and with members of the FBI and the Homeland Security Department, acted.

10, 9, 8, 7…the countdown by people filling the parks began just before midnight. 6, 5, 4…tonight it did not lead to a rocket hurled into space to conquer other planets or replicate New Year parties where merry-makers wearing funny hats hoist champagne glasses. Tonight’s attire of choice was not an astronaut’s suit or an evening gown or suit, for here the fashions preferred were bandanas worn around the face and gas masks, in preparations for a different kind of festivities. Still, at midnight, a cry of joy was raised.

Hundreds of occupiers and their supporters, along with curiosity seekers, gathered, joined by several hundred policemen and policewomen and even a few horses. The police preferred to emulate the outfits of Star War’s Imperial Storm Troopers, while the horses were naked. Starting at midnight, those sworn “To Serve and Protect,” advanced towards the crowds. I tried talking with several, urging them to remember that it is their brothers and sisters that they are facing with their weapons, but they remained silent. Intermittently, a warning was broadcast, a threat to use “physical force and chemical agents.” Police Chief Reese, who saw in this confrontation a chance to catapult into the mayor’s seat, was commandeering his troops, while the mayor preferred to stay away. I joined the bicycle contingent, about fifty of us circling the blocks, slowing traffic, riding around and around. The Israelites circled the walls of Jericho seven times before toppling them. We circled many more times, our bells and shouts replacing the call of trumpets. Later, I joined the crowd in the street. As the evening went on, tensions mounted. Several times, baton-wielding cops marched forward, preferring the Spartan phalanx, a formation favored by ancient Greek warriors, but the determination of the multitude, pushing against them, held, and the police withdrew. At three in the morning, people started drumming, singing, laughing, dancing, and I too.

The sense of our power, our collective power, remained with me as I rode my bicycle home at dawn. Passing by homeless people sleeping under highway overpasses and bridges, the mayor and Portland Business Alliance’s concern for “health and safety” not extending to their welfare, and then by the waterfront, along several large tents hosting the Cavalia Horse show, where acrobats fly in the air above galloping steeds, I thought of the horses that earlier were directed at peaceful protesters. Riding in the deserted streets, a sliver of a moon above, I felt elated. 10 hours later, taking advantage of the our fatigue and smaller numbers, the police, employing pepper spray and batons, destroyed the camp, and surrounding it with a fence, have stationed guards at all corners.

2012

The rage and hope expressed by the Occupy movement are part of a long history. Among the many antecedents and trailblazers, here and around the globe, are visionaries and warriors such as Thasunke Witko (Crazy Horse,) Frederick Douglas, Emma Goldman, Lucy Parsons, Mother Jones; groups such as The Diggers and the Levelers, the IWW, and the Freedom Riders, and many acts of rebellion, resistance, and re-building. Will the Occupy movement build on the wisdom and hard work of previous generations while adding new insights and visions, to insure individual and planetary survival? This remains to be seen. It is now a time of gathering forces, taking stock of success and failure, educating ourselves and those who are part of the 99% but are still on the sidelines, figuring what is next.

In this quest and struggle, activists, workers, rebels, artists, and writers, can teach us much, as they too have imagined a different future and a different world. Lorca wrote of a time when on the center of global capitalism:

Cobras will hiss on top floors.

Nettles will shake courtyards and terraces. The Stock Exchange shall become a pyramid of moss. Jungle vines shall come in behind the rifles

And all so quickly, so very, very quickly.

Ay, Wall Street.

Across from the destroyed Portland encampment site, looms the gray eight-story glass and cement jail. Chiseled into its entrance gates are Martin Luther King’s words “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” The words are from his Letter from Birmingham Jail, where he was imprisoned for protesting the city’s government and merchants’ segregation policies. Responding to white Alabama clergymen who, advocating patience, claimed that injustice must be opposed only in the courts, King answered: “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly,“ and stressed using forceful nonviolent direct action in order to bring about change, for “justice too long delayed is justice denied.” The task of establishing the new world we desire and which we carry in our hearts is an arduous one, but one that can no longer be denied, and one on whose path we are resisting, dreaming, and dancing.

Nicaraguan Rosario Murillo, Sandinista fighter and poet, who has lived and fought during times of dictatorship, foreign military intervention, and revolution, hailed in “I’m Going to Plant a Heart in the Earth” what is possible:

A heart.

that won’t leave some to one side

and others on the floor in fractions.

a heart that has no country

that knows no borders

a heart that will never be fired.

a heart, unnerving, unnamable

something simple and sweet

a heart that has loved.

by Alon Raab