Plaça de Sant Felip Neri, Barcelona, Catalunya, Espanya.

Text and photos by Pete Shaw

October 17, 2018

Dear Cyndy and Josh,

La memòria és important.

Plaça de Sant Felip Neri is where a piece of canvas comes to life.

Nearly two weeks ago we were in Madrid’s Reina Sofia, a former hospital turned modern art museum. It houses Picasso’s “Guernica,” that masterpiece of horror and chaos. Its inspiration, found in Franco’s Nazi friends dropping bombs, was a near-completely civilian target composed mostly of women and children. Some people claim the bombing served no military purpose as Guernica’s only real military target was a factory on the edge town which made some items used for making war. But as with most bombings, the ultimate purpose was to terrorize people.

In early 1938, about nine months after Guernica, Franco’s forces had laid siege to Barcelona. The church in this square, also Sant Felip Neri, had and has an associated school. On January 30, 1938 many of its young students, along with some refugee children from Madrid (the church was also used as an orphanage), sought a haven from Franco’s bombs in the church. His forces landed one on the church, killing 30 people, most of whom were children. People came to help. As they were trying to rescue survivors, Franco’s men threw in another bomb, this time hitting the square, killing 12 more people.

As I sit here, school is over for the day. Many groups of children are in the square, which the school uses as a playground. They are sitting in small groups, or running around, or playing with a ball. They are doing the things children should do. Their elders talk. I appear to be the only touristy sort settled in here. I certainly don’t see many people walking through, confused, wondering where the footwear museum went (it closed three years ago). I have not heard any English, although I imagine if I did, it would probably be someone asking how to get somewhere else. Behind me is one entrance to the square, and a steady stream of people have been coming through, heading toward another opening, opposite the church, through which they will pass on their way to elsewhere.

As I sit here, school is over for the day. Many groups of children are in the square, which the school uses as a playground. They are sitting in small groups, or running around, or playing with a ball. They are doing the things children should do. Their elders talk. I appear to be the only touristy sort settled in here. I certainly don’t see many people walking through, confused, wondering where the footwear museum went (it closed three years ago). I have not heard any English, although I imagine if I did, it would probably be someone asking how to get somewhere else. Behind me is one entrance to the square, and a steady stream of people have been coming through, heading toward another opening, opposite the church, through which they will pass on their way to elsewhere.

To my right is the wall of the church. I am not the sort of person who feels a terrible need to bear witness to objects. But today, it seemed important. I just read in one of the local papers that Archbishop Oscar Romero, who in 1979 was murdered in El Salvador by a US supported right wing death squad because he took seriously the words of Jesus, was made a saint. I presume this does not fly well with the more conservative Catholics and other professional Christians who by their actions clearly despise what Jesus stood for.

Plaça de Sant Felip Neri was a short walk from the taverna where I read that article, and so here I am.

A few hours ago, we were walking from the Gràcia neighborhood to this part of Barcelona–if not this precise square–where most tourists spend their time. Along the way we passed a display partially covering two stories of a building wall, featuring 60 portraits of children, each one about 3 feet square, ten across, six down. The drawings appear to be charcoal, black and white, save for one in the third row from the bottom, fourth column from the left, whose face is adorned with the colors of the Catalunyan flag.

Each drawing shows a unique face, yet all are clearly children. On nearly every portrait is written, “Why?” The question refers to the refugee crisis. Why are we letting children die? Why are we letting children die due to the results of crises that we have played a great hand in causing? The title of the work is “Mirades,” which in Catalan is the past participle of mirar, to look. It’s direct translation is Have you looked? I suspect a more accurate phrasing would be Have you seen?

When we were in Granada, we got to see Placeta Joe Strummer. He often visited Granada, and he mentions it twice in The Clash’s “Spanish Bombs.” It is not a gorgeous site, and while it is official and thus appears on tourist maps, it is probably less of an attraction than the Alhambra. There is one small marker of the small square’s name, and we had the place to ourselves. It was just us, the lovely cedar trees growing there, a small hand painted sign identifying the place, and a nice cat. Strummer is remembered by many there not just as an artist, but a person. I miss his art. People who met him remember a truly kind person who you would assume, if you did not know he at one point was a member of one of the world’s most popular and respected bands, was just some guy hanging out in a bar, shooting the shit with the other folks there.

As we saw “Mirades,” I was reminded of the refugees streaming from the violence in Central America that the US played a huge role in engendering and supporting. A clear line runs through Saint Oscar to this moment on the Mexico-US border. We are locking up children and tearing apart families. Again. It is as American as apple pie.

I have my doubts that the people of Catalunya would describe the refugee crisis as “tan espanyol com el pastís de poma,” but I would assume they have a similar aphorism. In my head, I heard Strummer singing, “Go straight to hell, boy. Go straight to hell.”

It is now late afternoon. The children are still playing. Along the 30 foot wall of the church are numerous blackened pock marks, indentations in the thick stone ranging in diameter from that of a quarter to significantly larger than the soccer balls which a few of the kids are now kicking around. The majority of these scars are found between ground level and about eight feet high. They are one result of Franco’s bombs. Some of the shrapnel hit the wall. Some of it rendered children and adults trying to rescue children into hamburger.

A couple of months ago I was reading about the debate regarding Franco’s corpse. It is buried outside of Madrid, in the Valle de los Cáidos–the Valley of the Fallen–a church and a monument to, as Franco declared, reconciliation. That’s sweet. It is something of a site of pilgrimage for quite a few of Franco’s supporters, known as Francoists. I imagine in Italy there are some folks who gather at the base of the tree from which Mussolini’s bullet-ridden corpse was hanged to pay their respects. Similarly at the sight of some bunker in Germany for Hitler, I would guess. Hell, in Portland, that Krueger creep, somehow still on the police force, has a thing for Nazis.

But these are all sort of underground things, albeit becoming frighteningly more emergent. Obviously, this includes back home. Such things never die unless you kill the cause. Here, because Franco and his forces not only won the Spanish Civil War, but stuck around ruling the country until he died in 1975, his legacy is a subject of debate. I assume it was not when he was in power, at least not publicly. That is certainly a few steps forward. It was recently declared that his body be exhumed from the monument’s mausoleum and be reburied elsewhere. I hold out hope that this is nice political-speak for “his body will be burned in a trash bin.”

But these are all sort of underground things, albeit becoming frighteningly more emergent. Obviously, this includes back home. Such things never die unless you kill the cause. Here, because Franco and his forces not only won the Spanish Civil War, but stuck around ruling the country until he died in 1975, his legacy is a subject of debate. I assume it was not when he was in power, at least not publicly. That is certainly a few steps forward. It was recently declared that his body be exhumed from the monument’s mausoleum and be reburied elsewhere. I hold out hope that this is nice political-speak for “his body will be burned in a trash bin.”

There is an independence movement afoot here in Catalunya, independentisme català. There has been for quite a long time now, and every so often it gathers steam. About a year ago, in fact, Catalunya declared its independence from Spain, and as a result of the Spanish government essentially declaring Catalunya’s leaders criminals, some of those leaders went into exile, while others were imprisoned. Tomorrow there is a rally demanding the release of all political prisoners.

It seems in Barcelona that everywhere you look you see the flag of Catalunya. It is painted on walls. It hangs from the balconies of apartments and offices. It has long been a component of FC Barcelona’s coat of arms that adorns the hometown futbol heroes’ uniforms. Number 10, in particular, that of the great Lionel Messi, is a hot item, both as souvenir and sacrament. These displays, outside of the jerseys, are often accompanied by signs ranging from demands for independence to freeing political prisoners; from insistence that the government respect human rights to the details of what those human rights are.

It is complex stuff, as one would expect. However, at its base, its values appear egalitarian. Among those flag adjacent signs, as well as appearing on various posters and graffiti, are calls to fight fascism and all its attendant bigotries. I understand you cannot put much stock in quantifying support through such displays. But the fact remains that with every few steps, you encounter these messages on doors, on walls, on windows, on walks, on curbs, on streets. Some appear older than others. Some are. Nobody has taken them down.

Throughout this trip I have talked with only one person who does not support those seemingly bedrock principles of much of the independence movement, although I admit my sample size is not large. Of course, there is an anti-independence movement. I had a hard time finding it, but all that means is that I was not looking in the right places. In recent years, polls have shown a fairly constant support for independence, usually clocking in around 40%, although in a few cases, topping 45%. However a majority of people support Catalunya remaining a part of Spain, with them about evenly split between Catalan being a federal state within Spain, and it being an autonomous community within Spain. I am not sure what those mean or their distinctions, but they are clearly different from creating an independent country of Catalan.

But of the people I met who support the movement, all of them do so with intense caveats. First, they all seemed to make clear, they do not trust the central government. However, they also are not that trusting of the people who have come to lead the movement. They regard them as opportunists–I suppose what we would call grifters. They tell me these people don’t care about independence as an ideal, but rather, a way as to not be held accountable for various white collar types of crime, and a way out of paying taxes. One woman, who supports the movement, told me she was worried that it was being taken over by people much like Donald Trump, false prophets of populism out only for their own good and gain. The one person I talked with who opposed the movement, expressed the same worry.

The town that sings never dies.

I cannot comment much further than that. What I do know is that there is active organizing going on here. With Spain’s history of fascism–and for many, a fondly remembered one–that is no surprise. People felt its boot on their necks here. They remember. Through the years, their unauthorized stories have survived alongside the official narrative. It is a high order of resistance and resilience. Looking at the news from home, this history fills me with dread. But those who organize and struggle against this rising tide of fascism bring me hope.

The children and their guardians are starting to leave. A few want to stay, but their side of the square is emptying.

Franco’s forces tried to cover up the bombings. The marks in the stone, they lied, were due to stray bullets fired by anarchists as they executed church priests. But there were witnesses, alive and dead. One need not put one’s finger into the smaller print of the shrapnel or thrust one’s hand into the much larger gaping wounds it also left in the side of the church to believe that 42 people were murdered here. When the church was rebuilt, it was decided to keep the wall as a reminder of what happened not so many years ago when other people’s children hoped they might find sanctuary from fascism.

Memory is important.

Abraçades i amor,

Pete

Sagrada Familia.

October 19, 2018

Dear Dad,

It is quiet in Madrid. It is probably quiet in most places at 3 AM, but I suspect the silence here is a lot due to spending our last night in Spain in an attic apartment in the middle of a neighborhood, far from the main drag’s many clubs. It is tempting to go outside and walk up there, but what would I do? In a few hours we will begin our long journey home. By the time we return we will have devoted nearly 24 hours to the task, and I will be utterly useless as a human, functioning or otherwise. No, quietude is the better choice. Especially after four days in Barcelona.

I wrote in an earlier letter to you that Madrid aspires to be Paris. I suppose you might say something like that about Barcelona. Maybe better would be to say Barcelona has incorporated much of Paris, and then thrown in a lot of flair, an element of weirdness that has an air of Parisian haute couture, but musters up a strange boldness that gives Barcelonan culture a strain of something anarchic and otherworldly.

Not a far train ride up the coast toward France from Barcelona lies Figueres. It would perhaps be nothing more or less than any other workaday town were it not home to the Salvador Dalí Museum. That wonderfully strange man both was born and died in Figueres, and his body is buried in the museum.

The frontal facade of the building is topped with statues of people holding aloft lengthy loaves of bread painted gold, surrounding an erect copy of one of those old diving suits. Of course it is. Inside is a treasure trove of both his famed surrealist works, and at least to me, his lesser known, more classical style paintings. Dalí was an excellent technical painter, and to see those works in such close proximity to his surrealistic sketches, paintings, and other installations–including the heartbreaking one of the boat in which he and his wife spent some of their most precious moments–made for fascinating pacing. Bless that beautiful prince of the Freak Kingdom, and may his flag forever fly proudly. Easily the most fun museum I have ever visited.

Antoni Gaudí was a stone freak in his own right, designing the kinds of buildings Dalí might have had he gone into architecture. You come out of the Passeig de Gràcia metro station, and you are staring in the face of his Casa Batllo. It strikes you as unreal. Even on a block of strange-looking buildings–it is known as the Illa de la Discòrdia, The Block of Discord–it stands out. It has a skeleton motif (why not?), and it has some gorgeous stained glass, and its upper exterior walls are delicately painted with beautiful leaves, and that wall is also decorated with intricate tiles, and it really is nothing like anything you have ever seen. A few blocks away is his Casa Milà, which looks like series of stone waves with remarkably intricate, twisting and winding wrought iron balconies.

Casa Vicens

Gaudí was a Modernista architect, part of the Catalan Modernisme movement that extended to many other arts including painting, sculpture, writing, and design. When Barcelona needed to expand beyond its old boundaries in the late 1800s, it created The Eixample, or The Extension. And among the architects they set loose on it were the Modernistas.

Gaudí’s Casa Vicens is considered his “manifesto” design where he began developing his own style. It is a stunning building. It’s bright tiles and its strange sense of balance bear a distinct Moorish influence. It is not quite orderly, but it wants you to believe that it is. What better way to hide its surprises? Gaudí’s attention to detail was incredible, and in many of his houses, he even designed the furniture, much as Frank Lloyd Wright did.

Gaudí was a devout Catholic, and he believed that nature was God’s greatest creation. Architecture, he believed, should reflect nature. Among the fundamental components of his designs are lots of light and an aversion to straight lines, which Gaudí once noted, are not found in nature.

I suppose this is no more apparent than in his cathedral, Sagrada Familia, or Holy Family. Construction began on the cathedral in 1882, and Gaudí took over as chief architect a year later, changing the designs to suit his vision. It is still being built, and it is hoped the building can be completed by 2026, in time for marking the centenary of Gaudí’s death.

I’ve never seen anything like it. There are fewer pillars than in most other similar cathedrals. Using nature as a guide, Gaudí viewed the pillars as trees. Near their tops, he placed limbs that when combined with his innovations in using arches, enabled his pillars to bear more weight than the traditional singular column. The result is a much more open interior than you will probably find in any other cathedral of its size. Throw in the huge banks of stained glass windows, and you have something far more airy than any other cathedral I, and likely you, have ever been in.

The outside also is most impressive. The intricate carvings into the stone of the church of the Passion and Nativity Facades are both incredible and controversial. The Nativity Facade was completed during Gaudí’s lifetime, while the Passion Facade was finished only a few years ago. Does the Passion Facade reflect Gaudí’s plans? In one respect, no. It looks quite different from the Nativity Facade. But then again, Gaudí was constantly changing his plans.

I am not sure why it matters: to be in the cathedral’s presence is in some way to make the issue pointless. It is a beautiful work of art, and however slowly, it is unfolding before your eyes. When we went to the top of one of the towers along the Passion Facade, we could look down on the roof of the nave. Atop it were brightly colored ceramics and statues of large bunches of grapes and loaves of bread, representing the elements of the Eucharist prior to transubstantiation. Bread is life. As you know, for Catholics, transubstantiated bread offers eternal life. Looking out on Gaudí’s representations, I was reminded of the Dalí Museum and its many gold painted loaves of bread. Art, too, is life, and in its way, is eternal.

Many of Gaudí’s famous sites are located well within the tourist area of Barcelona. In some cases, they seem to define its limits. But the best place really to appreciate his work lies far off in Sarría, a somewhat posh community on the western outskirts of the city, rising at a moderately steep slope up the base of Mount Tibidabo. About an hour’s walk from Sagrada Familia–and significantly further from the restaurants and souvenir shops of Barcelona’s waterfront and nearby old neighborhoods, and the relatively flat land upon which they lie–I suspect for the average visitor to this beautiful city, the approach appears hostile. That assumes Sarría even lies on most wayfarers’ itineraries.

You will not find postcards here.

But you will find Torre Bellesguard on the grounds that once held a 13th century palace. Gaudí was commissioned to make a house using its remains–a few walls and the patio–as a guide. There are most of Gaudí’s hallmarks: the tiles, the crushed ceramic mosaics, the wrought iron, and the attention to detail down to even arranging by color and how that color would reflect the sunlight at different times of the day, the stones used to build the walls. Wanting to pay tribute to the original medieval structure, Gaudí used far more straight lines than usual. He then designed rounded frames for the windows, placed rounded drainage pipes on the walls, and as well, softened the ascetic look of tower’s parapets. The mesmerizing result is a seamless combination of Gothic and Modernisme.

Did I mention the roof looks like the head of a dragon?

Did I mention the roof looks like the head of a dragon?

Unlike Gaudí’s more well-known sites, Torre Bellesguard bears glaring scars of time. It is a little over a century old. Some of the tiles on a small structure near the fort’s entrance are chipped or have been stripped away. A couple of long benches look worn. Other areas of the grounds are far from the majesty that has been restored at other Gaudí buildings. Unlike them, Torre Bellesguard does not receive funds for being a UNESCO Heritage Site or some other recognition of historical importance, so the blemishes remain in full view.

But there is something about this that makes for a charming experience, one which for nearly the full 90 minutes we spent there, we had to ourselves. The house and grounds have aged gracefully. This is not to say that Torre Bellesguard is decrepit. The house has been taken care of, and some its exterior, including a couple of small benches with crushed ceramic tiling near the front door, have been restored. Side by side with both the glaring and more subtle ravages of time, the site offers a greater appreciation for the fine craftsmanship of the people who brought to life Gaudí’s, as well as their professional descendents who have refurbished his work. It is something I suspect most visitors to Barcelona don’t get to enjoy.

Refurbished or aged, Gaudí is Gaudí, which among many things is to say he is huge. His work certainly can be: Sagrada Familia and Parc Güell are large and expansive, and his presence is felt in all of the city’s architecture to a degree that I would be at all surprised if someone told me that architects have divided the history of Barcelona into BG and AG, Before and After Gaudí. Actually, I would be surprised if this was not the case. People from all over line up for hours to see his buildings (well, not at Torre Bellesguard), and even in Parc de la Ciutadella, you will find crowds of people gazing for long periods of time at the helmeted lamp posts that he designed long before he made his mark on the world. The place is going to be a madhouse when Sagrada Familia is officially opened in 2026.

For many, he–his work–is the reason to come to Barcelona. That is a fine reason, and it certainly was one of mine. But in the end, I find the greatest rewards come from talking with people who live where we visit, getting to know a little something about them and how they navigate their world.

A few hours prior to catching yesterday’s train to Madrid, we had breakfast at a small place down the street from where we were staying. The day before, we grabbed a quick lunch snack there and got to talking with the two waiters, Albert and Camilla. They are nice people, as I would expect. Camilla both days was wearing vibrant colors, including the flower in her hair. Her personality is even brighter. She is genuinely friendly. Albert wants to visit New Orleans–which I told him was an excellent idea–and enjoys jazz, particularly John Coltrane, for whom an edifice along the lines of Sagrada Familia surely is in order.

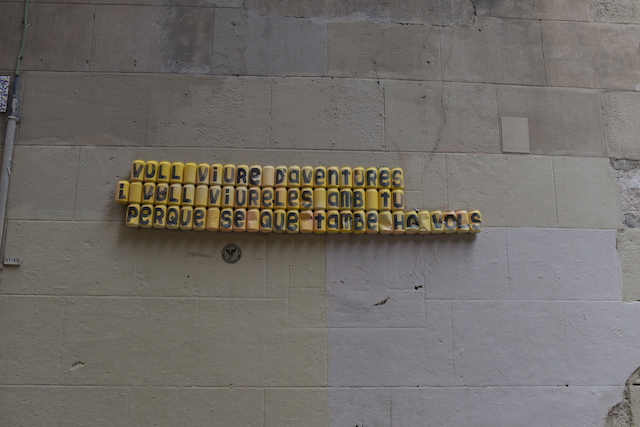

Mon Bestica, I want to experience adventures and I want to live with you because I know you also want to.

With them, in Spanish and English–with the occasional query as to how to say something in Catalan–we quickly found ourselves engaged in the so-called small talk that is the mortar of any meaningful relationship. It is the difference between asking rhetorically, “Com està?” and posing that question because the answer bears great weight. It is the difference between answering, “Bé, gràcies, i vostè?” and immediately following it with, “¿Tienes un menú en inglés?”, and taking a genuine interest in Camilla’s reply to the first.

It is taking obvious joy in talking about Coltrane and his music, knowing full well your Spanish, never mind your Catalan, will not come close to your English in describing it. It is making connections between what you have felt while seeing, listening, tasting, touching, and most of all, Loving, in Barcelona and Córdoba and Sevilla and Granada and Madrid, and how those feelings have been influenced by all you have known before and will influence all you feel hereafter.

It is wondering what the future will bring, a future that with all seriousness includes a promise that should Camilla and Albert ever find themselves in Portland, Oregon–or wherever we are–they will be welcomed as Friends.

However poorly pronounced, it is saying, “Adéu,” to people you feel lucky to have met. And then against all odds, entertaining the hope that one day we will meet again.

Love,

Peter