Photo by Kendall

Story by Pete Shaw

“And to those who silence and erase survivors, I would like to say, ‘Never question what someone else did to survive in the face of such trauma. Instead, question the assailant. Question the system. Question rape culture. If you are blaming the victim, you’re on the wrong side of the issue. Question yourself.’”

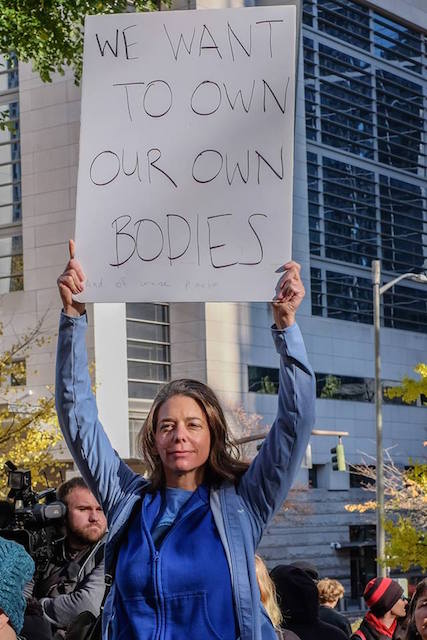

Those thoughtful and powerful words were given by Popular Mobilization’s (Pop Mob) spokesperson Effie Baum, but she did not write them, and they are not hers. Whose words they are remains unknown to most. However, one thing was once again made clear on Saturday November 17 as Baum read them to a crowd of over 350 people gathered in Chapman Square: as deep as the problem of believing survivors of abuse may be, particularly those who are not white men in positions of power, the trouble is even more profound.

The most recent obvious example of this is Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation as a justice of the Supreme Court, despite Dr. Christine Blasey-Ford’s bravely coming forth and testifying that Kavanaugh sexually assaulted her. Kavanaugh’s rebuttals were a series of outright lies interspersed with the hysteria. Kavanaugh made it through the Senate Judiciary Committee and was soon confirmed. Blasey-Ford’s courage, while presented in a much more high profile situation than most survivors will ever experience, was hardly unique.

Many survivors spoke or were spoken for at Survivors Are Everywhere: A Survivor Shout Out. Their stories were part of Pop Mob’s Shout Your Story project which centers the experiences of survivors and seeks to counter the right wing narrative that men are in constant danger of having their lives ruined by false accusations of sexual assault.

Those fears are nonsense. For example, studies have consistently found that only about 5% of rapes experienced by college women are reported to the police. When all women are included, the number rises only to 10%. In other words, 95% of college women and 90% of all women do not report their rapes to the police. Furthermore, they may also not report their rapes to researchers, so the rate of non-reporting is likely higher. According to University of Colorado, Boulder professor Joanne Belknap, although 5% of rapes reported to the police are false claims, “the fact that at least 90% of rapes are never reported to the police suggests that of all rapes, 0.005% are false allegations.” Belknap goes on to write that “although false rape claims are reprehensible, it is important to acknowledge that they are also incredibly rare. Clearly, as a group, victims are very unlikely to report rapes to the police, and even less likely to make false claims.”

Photo by Pete Shaw

But as Baum noted, people “are not moved by statistics” which “do not hold the same emotional charge and power that narratives do.” And in a place and time where the few women who report their rapes are often blamed for the assaults on their bodies or are simply not believed, telling your story is a radical and courageous act. It is part of surviving. It is a deed worthy of celebration.

Marie, whose story was among the many collected by Pop Mob and was read aloud on Saturday, had long worried that if she told her story, she “would have lost everything.” Marie has engaged in “survival sex work,” and she continues doing sex work. On Christmas Eve 2016 she met with a client who had been screened and who told her the encounter would prove “gratuitous, it being the holidays.” In the end, “it turned sour. I was sodomized and dropped off miles from home with no pay. I was reminded that I’d be arrested if I reported the rape. As a sex worker, you have no one to turn to if you are a victim of theft, assault, or rape.”

The rape survivor quoted at the opening of this article, who wishes to remain anonymous, was given voice as she described the anger she felt toward herself “for not having the fight or flight response” and professed that she did not want to share her story because she thought she could have done more to prevent her rape. But now she has reached a point where telling her story is empowering.

“However,” she said, “now that I have learned more about rape and the psychological responses to rape and trauma, I can thank my body and my mind for doing what they needed to do in that moment to survive. I see my resilience and strength following the attack, and feel empowered knowing that it did not break me. Although it was the worst thing that ever happened to me, I feel a sense of safety knowing how strong and reliable my mind and body are in the face of danger and trauma.”

No matter what form it takes, survival is a radical act. A 24 year old woman whose name was withheld, submitted her story to Pop Mob which was read at Saturday’s gathering. She had been in “a dangerous relationship” in which she survived “frequent unprovoked violence, severe isolation, and sexual abuse” and also “survived multiple sexual assaults that should have killed me.”

“In July 2018,” she continued, “I survived a stroke as the result of domestic violence. I survived to witness a stranger harass a family that was abusing me to exploit my unpleasant reality. I survived my abuser’s family exploiting a strange man’s interest in me to protect themselves. Despite all of the damage my abuser inflicted on my precious brain, I am still all here. Just yesterday I testified against my abuser as he sat in the courtroom staring. I was granted a PFA (Protection From Abuse order). There’s an ongoing police investigation regarding sexual and aggravated assaults executed by my ex-boyfriend. Confronting my abuser continues to be one of the most difficult things I have ever done. It is absolutely heartbreaking learning how common and normalized domestic violence is. My medical condition feels minor in comparison. The abuse I endured continues to plague my daily life and recovery. Those responsible continue to do everything in their power to silence me. Regardless, I survive. If owning my dysfunction, being unashamed of the ugly truth can help save someone else from domestic abuse, I am proud I survived. Authenticity reigns.”

Another problem with facts is that when they come up against ideology, it is ideology that often wins. Kat, who emceed Saturday’s event, noted that this can and will change. “Capitalism,” she said, “is a powerful tool used to uphold patriarchy and vice-versa. These systems are inextricably linked and used together as cudgels to oppress women everywhere. The system isn’t broken. It’s working as it was designed to work. When we have blatant sexual predators getting elected to our most revered institutions, maybe it’s time we stopped revering them and start dismantling them instead.”

Patriarchy, as well as sexual and domestic violence, however, are not the only bigotries attendant to capitalism, and Saturday’s event sought an even greater inclusiveness to the idea of what it means to be a survivor.

Photo by Pete Shaw

“We are survivors in so many senses of the word,” said Baum. “Many of us are sexual assault and abuse survivors, but many of us are surviving every day as members of communities that are under continual attack–women, queer, trans, and non-binary folks, Black and Brown people, Muslims, Jews, undocumented folks–we are all surviving in this country at a time when we are in an ideological war being fought at the intersections of our identities and lives.”

That kind of solidarity is important at any time. Trump and his white supremacist allies are not just seeking to silence and discredit survivors of sexual assault, domestic abuse, racist attacks, and other forms of violence toward people and communities they feel should be seen or heard. Beyond the attempted gagging of survivors, white supremacists are also working to erase trans identities, control the bodies of women and people of color, and most obviously at the Mexico-US border, criminalize families and individuals seeking safety, often from horrific conditions that are a direct result of US economic and foreign policy.

The recent elections saw people fighting back. On the national level, Sharice David in Kansas and Deb Haaland from New Mexico became the first indigenous women elected to Congress (with David being the first openly queer congresswoman from Kansas). Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar from Michigan and Minnesota, respectively, are the first Muslim women elected to the House of Representatives. And in Massachusetts, Ayanna Pressley will become the first Black woman to represent that state in Congress.

Locally, JoAnn Hardesty will become the first Black woman City Commissioner. Just as significant as her victory, Hardesty, a long-time advocate for Oregon’s Black community, police accountability, and people without housing, defeated a candidate whose values were much more in line with the neoliberal capitalist ones that for too long have guided the Democratic Party.

However, in the long run, electoral politics is not the answer. Education, organization, and mobilization offer far greater possibilities–but as well, far more difficult work and longer range strategies–and just as the election of Donald Trump brought to the surface the simmering currents of white supremacy that have undergirded the United States since its founding, it also brought into the light the work of people who for many years have been combating it.

Saturday’s Pop Mob event was part of that fight. It was called in response to a white supremacist Patriot Prayer gathering taking place in Terry Schrunk Plaza, focusing on the nascent Him Too movement that developed as more and more women began summoning the courage to tell their stories. Indeed, men too are victims of sexual violence–1 out of 6 men are sexually assaulted in their lifetimes–and the Pop Mob event made note of this. In fact, that statistic shows that men are more likely to be sexually assaulted than to be wrongly accused of one.

The contrast between the two groups was glaring. Pop Mob, whose rally was joined by a large contingent of the Portland branch of the Democratic Socialists of America, was seeking not just to honor the stories and lives of survivors, but to expand the idea of what it means to be a survivor. Meanwhile, Patriot Prayer’s event, which was one of a few such events organized around the country, was severely narrowing the definition in accordance with its fascist, white supremacist ideology.

And where Pop Mob continues bringing more people out to fight fascism and white supremacy, the Patriot Prayer rally saw at most 30 or 40 people who oddly enough seemed to be keeping a fair amount of distance between themselves. From afar–it had to be viewed from a distance because despite Mayor Ted Wheeler’s failed attempt to ram through an unconstitutional ordinance that effectively would have required his permission for the Pop Mob protest, or any counter-protest, to take place, the police set up a barrier at the south third of Chapman Square and later banned people opposed to fascism and white supremacy from even being on the sidewalk abutting Chapman and facing Schrunk–it looked more like a kind of performance art bringing to light the structure of slice of Swiss cheese.

Photo by Pete Shaw

As Baum pointed out, Patriot Prayer and other white supremacist groups such as the recently declared extremist gang The Proud Boys are part of a much larger problem that highlight the need for the continued grassroots organizing that supports all kinds of survivors.

“These movements,” Baum told the crowd, “are fighting to be heard for visibility and justice, for women, for queer and trans communities, for immigrants and the caravan heading toward us even as we stand here. For Black Lives, for Standing Rock, for the missing and murdered indigenous women. For all of these experiences and stories that are being brought to the forefront.”

Where fascist white supremacist groups continue their longstanding tradition of questioning the oppression that their ideology visits upon others, groups like Pop Mob are furthering a model that responds to all survivors by saying, “We believe you.”

Hadie, from Sierra Leone, is a mother of three children. She is a teacher and a child care provider. “Something bad” happened to her on January 4. Hadie reported it, but was told, “There’s not much we can do…we’ll wait for another time.”

She found it difficult to tell her story to her community, something common among survivors. “I am telling you,” she said, “coming from an African community, I can’t really tell my story because if I do, I will be judged. There will be lots of questions. People will be asking so many things.”

Understandably, Hadie could give into despair.

“I guess someone has to go through what I went through before they believe me,” she told the crowd. “And then maybe–then maybe–they will listen to our cries, they will hear our pain. But my pain is real, and it should be acknowledged. I ask myself every day, Why is he getting away with it? I thought they said if you report it, you have done the right thing. I have been failed by the justice system.”

Resolutely, Hadie refuses giving into it.

“I tell you this: I will not be silenced. This is my body, and I get to say who should touch me and who shouldn’t. My parents are my strength, and I hope you are listening so you can do it right for me. I have been failed by the justice system, but I will not keep quiet. My body is mine, and this is my truth.”

Believe her.