Story by Pete Shaw

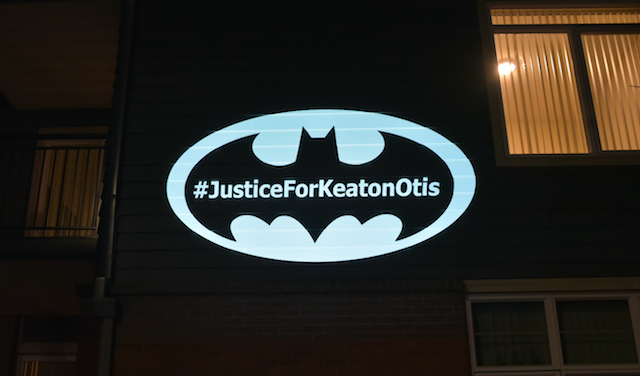

The corner of Northeast 6th and Halsey is hallowed ground. It is not the site of a mosque or a temple or a church or any other house of worship. There have been no reports of visits by the Blessed Virgin Mary or other religiously affiliated revelations, whether out of thin air or seared into a bun from a nearby restaurant. Nonetheless, the patch of sidewalk is something approaching sacred to those who gather here at 6 PM on the 12th of every month, as they have since June, 2010.

A month earlier, on May 12, 2010, Portland police racially profiled Keaton Otis, a 25 year old Black man who was driving in the Lloyd District. A team of three Portland police serving on the Hotspot Enforcement Action Team (HEAT) pulled over Otis and were soon joined by four more HEAT officers. Minutes later, Otis was dead murdered by the Portland police in a hail of 23 bullets. It is difficult to view video footage of the shooting and consider it anything other than an execution. Later, Officer Ryan Foote would say he pulled over Otis because “He was wearing a hoodie…He kind of looks like he could be a gangster.”

Nearly nine years later, none of the seven police officers involved in Keaton Otis’s murder have been held accountable.

A month after Otis was killed, his father, Fred Bryant, began holding a monthly vigil in memory of his son, and all those murdered by police. Bryant was tireless in his pursuit of justice for his son, but he never gained it. Bryant died on October 29, 2014, and while it would not be considered proper form for a death certificate, it would not be inaccurate to say the bullets that killed Keaton Otis eventually took Bryant’s life as well

This month’s vigil, held on a cool Saturday night, was attended by over 25 people. While the Trailblazers had the evening off, Saturdays offer enough opportunities for entertainment that you would be forgiven for thinking only a handful would attend. That’s what Kent Ford, the venerable activist who in 1969 helped found Portland’s Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, thought he might find. All the same, he was not surprised at the showing, and when his turn came to explain why he was there, he offered a few snapshots of his history that reminded people that when you organize and persist, you win.

Still, nine years after the Portland police murdered Otis, and about 4.5 years since Bryant died, people continue the vigil. This is where they assemble. Some come for consolation. Others console. This is where they offer testimony, community, prayer, and all other manner of hope for justice for Keaton Otis, Fred Bryant, and all victims of police violence. This is where some find peace, even if only momentarily. This is where memory and hope intertwine, holding the past close while reaching for the future, each informing the other. This is where love congregates.

This was the first observance since Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty took office. Hardesty has long fought for racial justice and police accountability, and without meaning to rank people’s involvement she was one of a few people–including Otis’s sister and Bryant’s daughter, Alyssa–instrumental in making sure the vigils continued in the months following Bryant’s death.

More starkly, another name was recently added to the all too lengthy ledger of those murdered by Portland police. On January 6, Andre Catrel Gladen, a 36 year old Black man and father of five, was gunned down. Gladen was in town from California, visiting family. Some of his relatives say Gladen had paranoid schizophrenia. He was also legally blind. According to an article by Maxine Bernstein in the Oregonian, Gladen had been pounding on the door of a stranger’s home in Southeast Portland, looking disheveled, telling Desmond Pescaia, who lived there, that someone was trying to kill him. Pascaia offered Gladen water and money to grab a train and get some food. Gladen would not leave and ended up falling asleep on the porch. Pescaia soon called the police, and after a brief tussle and pursuit in an attempt to handcuff Gladen, that included Officer Consider Vosu firing a Taser at him, Gladen reportedly pulled out a knife (this claim has now proven controversial) and approached Vosu. Three shots later, Gladen was down. After arriving at a local hospital, Gladen was declared dead.

In 2012, the Department of Justice (DoJ) issued a report regarding how Portland police respond to people experiencing or appearing to experience mental crises. The original impetus for the DoJ investigation came from the Albina Ministerial Alliance, which in June 2011 asked the DoJ to examine how the Portland police interacted with people and communities of color. The DoJ punted on that issue. In its account, the DoJ concluded that the Portland police had “engaged in an unconstitutional pattern or practice of excessive force against people with mental illness,” finding “instances that support a pattern of dangerous use of force against persons who posed little or no threat and who could not, as a result of their mental illness, comply with officers’ commands.” As well, the DoJ found that the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) employed “practices that escalate the use of force where there were clear earlier junctures when the force could have been avoided.”

While not the focus of its report, the DoJ nonetheless noted “the often tense relationship between the PPB and the African American Community,” stating that some members of communities of color “perceive” a pattern or practice of “bias-based policing.”

Well, that’s not entirely true. As Dan Handelman of Portland Copwatch noted on Saturday night, in the 99 days between when Portland police killed Patrick Kimmons and Gladen, they “were involved in seven deadly force incidents, which is more than any single entire year since James Chasse was killed in 2006.” Chasse was murdered by Portland police while experiencing a mental crisis.

The Settlement Agreement between the City of Portland and the Department of Justice was supposed to reign in police violence. It has not. After a long series of meetings by a toothless Community Oversight Advisory Board, which absurdly included members of the PPB, little has changed

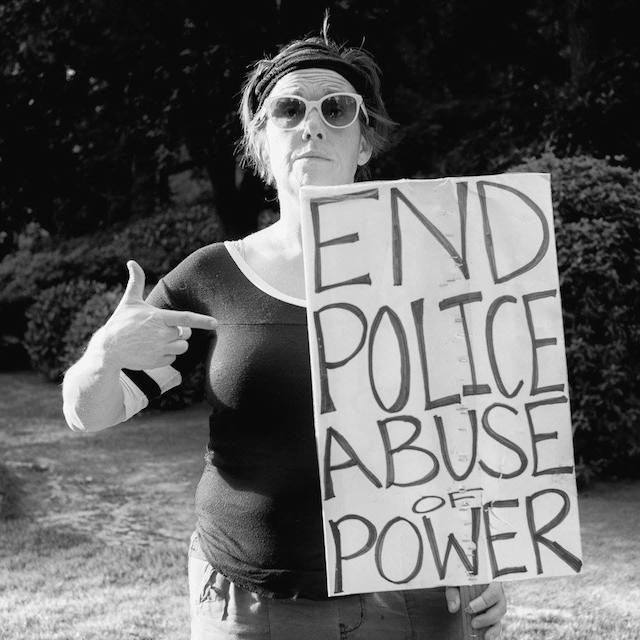

Frances O’Halloran, whose son grew up with Keaton Otis, wondered how long it would be before Portland’s leaders began holding the PPB accountable. “What is most obnoxious to me,” she said, “is that the City leaders can continue to pretend like they don’t see. There’s community outcry after community outcry, and I’ve seen community outcry for 50 years now, and they’re still pretending like they need more data, more information, more whatever, when they already know what’s going on.”

Christina noted a similar lack of progress–along with resilience in the face of its paucity–stating, “PPB has not taken any steps whatsoever with their officers, with their reactions to these killings, with the way they handle protesters. And I’m really tired of it. It’s amazing that we’re still out here, and it says a lot about our community here.”

Talking about the similarities between Gladen’s death and the deaths of so many others at the hands of the police, Elizabeth Sullivan said, “He was just a young man too. He was living in Portland for nearly a month, visiting his family. He lived on this earth 36 years. He fell asleep. He was disoriented. He didn’t have his shoes on. He soiled himself. It was last Sunday. They called the police, and the police come out. They send one lone rookie cop. No behavioral unit. And within a few minutes, he’s dead–three shots. And for what? Where’s all this money we’ve put into, you know–nine years later, the same thing. If you get a call that there is a man sleeping without shoes in the rain on somebody’s porch, you’re gonna send a cop? A lone cop, and he’s going to wake up just like magic and be like, oh sure officer, I’ll cooperate.”

Gladen’s death, by Charles Johnson’s reckoning, occurred at the intersection of people of color experiencing mental crises and being subject to the violent whims of the Portland police rather than receiving help from those equipped to handle people going through such crises. “When it’s mental health in white people,” Johnson said, “it’s why we didn’t kill you when trying to apprehend you, but if you’re a person of color, particularly a Black male, we basically had to kill you because of your mental health.”

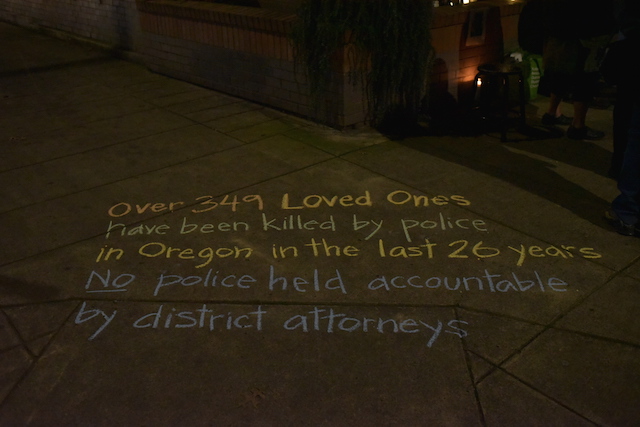

Handelman later added that in Oregon last year, police were involved in 35 deadly use of force incidents. That’s a 40% increase over the average of 25 police killings a year between 2010 and 2017. One might be inclined to assume that this growth is somehow a result of Donald Trump’s policies and white supremacist predilections, but Handelman noted that the uptick is not being seen across the nation. “It’s only happening here in Oregon,” he said. “We gotta figure out what’s going on.”

Between the oval formed by attendees lay 19 hearts, each one surrounding the names of some of those murdered by Portland police. Maria Cahill of the Pacific Northwest Family Circle, an organization working “to prevent Loved Ones from being harmed or killed by educating the public and changing laws and policies” spent nearly an hour kneeling on the sidewalk, chalking those names and the hearts ensconcing them. It was an act beautiful in its simplicity, its belief that these lives mattered, and the offered comfort that the lives of those who continue on in this world with the barbs of their losses forever embedded beneath their skin will always find others willing to walk with them as needed.

“We have to educate the public,” Cahill said, “and we can’t forget the loved ones’ names, our loved ones lost to police violence. I chalk names to raise awareness and to support the families of loved ones.”

Some arrived late to the vigil. They had been attending another one, this for Kimmons. The police murdered the 27 year old Black man on September 30, 2018, shooting him nine times, including from behind. The officers, Sgt. Garry Britt and Officer Jeffery Livingston, were determined to have acted in self-defense and a Multnomah County grand jury did not bring an indictment against them. The killing had an all too familiar pattern. Police kill a man, claim self-defense, and then are cleared, rarely, if ever, being held accountable. Along the way, they often work the media to drag their victims’ names through the mud.

June, who had been at the vigil for Kimmons, stated, “The police were harassing us there. They drove up to us to yell at us from their car that we needed to clean up everything before we leave; if we didn’t we’d be littering.”

June also stated that the police “continue to harass the Kimmons family in various ways.” That aggravation is hardly unique. Shelly Morgan’s son Bradley Lee Morgan, 21 years old, was murdered by the Portland police on January 5, 2012. At the time of his death, atop a parking garage, he had been suicidal. Two years later, the Morgan family filed suit against the city, essentially claiming that the police were not reasonably trained to handle Morgan’s crisis, and that lack of training contributed to his death. Shelly Morgan described police harassing her at her workplace. Because of their antagonism, the police are no longer allowed at her place of employment.

Morgan also described spending six years dealing with her feelings by herself. A year ago, she made her first visit to the vigil. It cannot heal wounds that can never be healed, but it has provided her with some sense of community.

That sense of community, to varying degrees, brings some of those people who have lost loved ones to police violence, to the corner of Northeast 6th and Halsey at 6 PM on the 12th of each month. Irene Kalonji, whose 19 year old son Christopher was murdered by Clackamas County Sheriffs on January 28, 2016, told her story, noting that one of the first people to reach out to her was now-Commissioner Hardesty. The vigil has provided some comfort, some way to move along with–not move on from–her son. Soon after Christopher was killed, she and Cahill “started planning our organization, Pacific Northwest Family Circle.”

It would be wrong to point out a leader of these vigils. Yes, on Saturday night, Cahill asked people to introduce themselves and state what brought them out. But the clear focus is on Keaton Otis, Fred Bryant, the 17 other names surrounded by Cahill’s chalk hearts, and all victims of police violence, both those deceased and those who carry on.

Perhaps fittingly, it is one of those survivors, Irene Kalonji, who closes the vigil. If it is ironic, it is also beautiful that her parting words are welcoming ones. This is, after all, hallowed ground, and the words spoken upon it should reflect both the sanctity of what is recalled here, as well as what has occurred on the twelfth of every month since Fred Bryant began this vigil nearly nine years ago.

“Everyone should come back next month. We’re so happy to see you.”

The vigil for Keaton Otis takes place on the 12th of every month at the corner of Northeast 6th and Halsey, from 6 to 7 PM. For more information, please visit: https://www.facebook.com/JusticeForKeatonOtis/