“So I continue to shout, Justice! Oh Justice! Where are you?

Because I remember.”

–Emmett Wheatfall

Anniversaries are time’s signposts. Marking occurrences stuck in amber, they retain life through their memories. As time beats on, they both reference and reconsider the formative events, reconstituting and redefining their truths. They provide an ever-shifting reevaluation of what once was, through lenses of what is, pointing to futures of what might be.

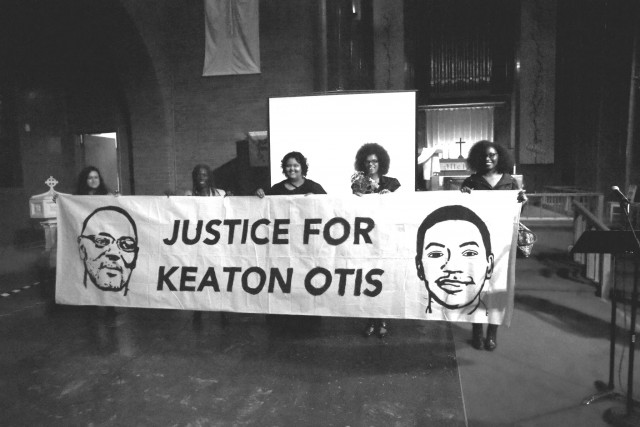

May 12 marked 11 years since Keaton Otis was executed by the Portland police. Gunned down in a hail of 32 shots from five officers, 23 of which found their mark, justice remains elusive for Otis, his family, his loved ones, and his community. And as has happened for the past many years, people gathered to remember both Otis and his father, Fred Bryant, and again to resolve to continue fighting for justice not just for Otis and Bryant, but all victims of police accountability.

The usual cast of the good and the great were present. And if for the second year in a row, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the internet feed of the event lacked the physical closeness that has often been found at the Maranatha Church’s inner sanctum, it still did not lack for the Love, compassion, and dedication that have always defined and propelled this commemoration.

One might be forgiven if ten years ago they asked themselves what the point was of this memorial. And one might well be absolved if one pondered the same five years ago, or even on May 12, 2019. But time is not linear, and achievements over time are never gained by singular movers and shakers.

I was not at the first memorial Bryant held on the corner of NE 6th and Halsey in the Lloyd District on June 12, 2010. Over the years, however, I have witnessed and partaken in a handful of them. Regardless of the crowd, sometimes small, sometimes spilling off the sidewalk into the street, they are moving both for what they mark and the resolve of those who mark them. Few of the attendees will make history textbooks, including some of the local luminaries whose innate restlessness for justice compels them to keep fighting when the odds seem so long.

I have often referred to that corner as a sacred spot. Not just because Keaton Otis was murdered there, and not because the people who gather together at the spot refuse to let his and Fred Bryant’s memories pass. It is sacred because those who congregate there carry the memories of Otis, Bryant, and all victims of police violence with them as they carry forth their work for justice.

I want you to understand that what may seem like repetition–what in many ways is repetition–takes place not at a singular point, but along a continuum composed of many discrete points.

My good Friend Walidah Imarisha, who has tirelessly labored to push that continuum, emceed the memorial. She is among many things a writer, her words chosen and her sentences crafted with great precision. And she never shrinks from Truth. Otis, she reminded the over 50 people who came together online, was targeted by the Portland police’s Hot Spot Enforcement Team “because he was Black.”

“They targeted him. They hunted him. And they assassinated him.”

In those horrific Truths, there is Hope. Perhaps more importantly, there is Resolve.

Ernest Hemingway once wrote what I find one of the most useful lines around, that one should never confuse movement with action. Nearly a year ago, when George Floyd was brutally murdered by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, all those seemingly freestanding points, those ostensibly untethered movements, exploded into action. Michael Brown. Sandra Bland. Eric Garner. Breonna Taylor. More locally, Kendra James, Patrick Kimmons, Aaron Campbell, Quanice Hayes. Their names and so many others, so often spoken, came together in an uprising calling not just for accountability, but for justice.

There has been some accountability. Chauvin was found guilty of his crimes, although there will be appeals. Other murdering police have been relieved of their badges, if not their guns. Some police forces are seeing some of their funding redistributed toward communities that bear the brunt of their violence. What once appeared bedrock grim reality, that police could hide behind the nonsensical and easily debunked claim that they serve and protect all people and communities, is now being questioned by a wide swathe of the population. It is now the people who steadfastly deny what their eyes and ears tell them, despite the immeasurable courage of people like Darnella Frazier who filmed George Floyd’s murder, who are exposed for their cowardly fealty to authority.

Dan Handelman, who has been in this fight with Portland Copwatch for nearly 30 years, sees some light. He sees it in the movie marquees proclaiming Black Lives Matter. It is there in the numerous bills seeking to reign in police. It is there in the fact that Portland police did not murder a single person from January 2019 to April of this year.

However, after three decades of work, Handelman knows better than many that optimism must be tempered. Those bills, he noted, are full of loopholes that could be used to maintain the status quo. And a month ago, the Portland police murdered Robert Delgado, who according to witnesses was experiencing a mental health crisis. Police murders of people in mental health crises were at the core of the US Department of Justice’s 2011 investigation of the Portland Police Bureau (PPB).

Handelman added that despite composing only 6% of Portland’s population, Black people represent 18% of traffic stops by PPB. The PPB claims one reason for that disparity is “people commuting into Portland,” but Handelman noted that the PPB “has not made any effort to count how many stops are of people from outside the city to prove this bogus claim.”

Handelman also noted that some data–although no data on this has been gathered by the PPB–shows that 32% of “the recipients of police force” in Portland are Black.

As to the uprising following George Floyd’s murder, Handelman stated, “It’s very telling that PPB’s analysis of last year’s protests blame the size and anger of crowds on bored people under the pandemic looking for things to do, rather than the systemic racism and brutality that led to the demonstrations and escalated as those protests were met with the same racism and brutality from the police.”

Irene Kalonji, whose son Christopher, while in the throes of a mental health crisis, was murdered by Clackamas County police on January 28, 2016–murdered by “seven officers in seven seconds”–clearly bears her burden. Yet she found the strength to co-found Pacific Northwest Family Circle (PNWFC), an “all-volunteer community group that supports Oregon and Washington Families whose Loved Ones were killed or injured by police officers” whose mission is to “unite Oregon and Washington Families to struggle on behalf of their Loved Ones for police accountability.”

Kalonji formed PNWFC with Shiloh Wilson-Phelps whose son Bodhi was murdered by Gresham police, 30 seconds after their arrival. “Life without him,” Wilson-Phelps said, “will never be the same.”

Meanwhile, the police who murdered her son were rewarded, given an award for valor and a raise. “They went from making $33,000 a year to $80,000 a year because they shot my son.”

I will not presume to know that Kalonji and Wilson-Phelps find healing in trying to help other survivors of police violence heal. I am not sure healing is possible in these cases. An old Friend of mine lost his child many years ago, although not to police violence. He recently told me that not a day goes by that he does not think about him and what their life together might have been. All these years later, there is still a sadness in his voice when he speaks of the son that would have inherited his name. He has stitched back together his life, but the wound has not healed. I suspect such wounds never do. And those memories of what was and those thoughts of what might have been, are long, sharp barbs forever caught in his, Kalonji’s, and Wilson-Phelps’ flesh.

I have seen Irene Kalonji speak numerous times both at the anniversary memorial for Otis as well as on the corner of NE 6th and Halsey. She never fails to mention Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty, who along with Jason Renaud, co-founder of the Mental Health Association of Portland stepped into her life while she was “in desperate condition–distraught, lost, confused.” Hardesty invited her to the vigil “at the place where Keaton was executed by Portland police.” She was inspired by Fred Bryant’s persistence. Her courage is as palpable as her pain.

Hardesty, whom Imarisha noted was one of the first high profile community figures who came out to support Fred Bryant, has long been a strong and noble voice in demanding police accountability and justice for the victims of police violence. She recognized that from so much grief, and the hard work much of it has engendered, there have been gains.

“Last year was,” she said, “a turning point in a lot of community members’ minds in the role that police play in our community, and the outsized role they’ve been playing for decades, especially as it relates to Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color. Last Summer, it was heartwarming to see almost 10,000 people almost daily, a 177 days of continuous protest, standing up for black lives, standing up against police brutality, standing up against police violence.”

However, she added that “some folks in positions of power seem to think last year was an anomaly, that we made it through last year. Made some budget changes, and therefore now everything is fine. But we have a lot more work in Portland to do to ensure that all community members feel safe interacting with law enforcement.”

Hardesty has proposed that some of the City budget be put toward a “truth and reconciliation process within the City of Portland.” She said Portland police chief Chuck Lovell has agreed to this truth and reconciliation process and “will require police officers to fully participate.” But as well, she also acknowledged the difficulty in dealing with a police bureau “that takes no responsibility or accountability for how they engage with Black and Brown and other communities of color, and the harm that consistently is done when you over-police communities at the expense of justice.”

Ultimately, Hardesty sees progress having been made, and urged people to continue making it. Bringing Bryant into the present, she stated, “I think Fred would be proud of what we’ve accomplished over the last 11 years, and I think he would be rooting us on to say, ‘Don’t stop now. Don’t slow down. We’ve got a lot more work to do. Let’s just keep moving.’”

Bryant, dead now nearly 8 years, still appears at these memorials. His presence remains commanding, even if confined to celluloid. In a clip from the film Arresting Power, Bryant spoke of his struggle to find justice for his son, and perhaps some peace for himself. I have seen the clip numerous times, Bryant struggling with tears as he talks about the Portland police and all those who have stood in the way of any accountability for those who murdered Keaton. Most movingly, Bryant speaks of his granddaughter, saying, “What they have left us with is that we have to explain why her dad ain’t here. You never get over that stuff. It’s imprinted into your spirit, your soul. So now it’s up to the family to explain what happened to her dad and to protect her from the forces that be.”

What never really hit me in prior years’ viewing of this clip was the depth of Bryant’s Goodness. He reveals that he has congestive heart failure, a condition exacerbated by the stress of his loss and his quest. It would eventually contribute to his death, brought on by the 23 bullets fired by the five police who murdered his son. His doctor told him to ease up, but on the issue of Keaton, he knew only one gear and one direction. He is clearly suffering on many levels. Yet despite his tangible pain, his gratitude for all those who have shown him Love and support is palpable.

Joe Bean Keller knew Bryant from childhood. Unlike Bryant, who found himself unexpectedly and unwillingly thrust into his cause, Keller had been involved in community activism for quite some time prior to his son Deontae being murdered by Portland police officer Terry Krueger on February 28, 1996. He expressed regret that he never sat with Bryant to urge him to ease up, to see that his struggle required, as is Keller’s motto regarding seeking justice for his son, faith and patience.

His understanding of the long arc toward justice is, understandably, deeply informed by his son’s murder. For the past few years at these anniversary memorials, his song and accompanying video, “Before There Was Trayvon,” has been played. With each passing year, its images of people murdered by police become more poignant.

Keller is to my mind the most intriguing “regular” at this event. He exudes a certain calm, a quiet, steely resolve. An intensity on a wavelength that carries far and wide, and if your ears are tuned right, you hear it, loudly. I always come away from hearing him speak with a deep respect for what I can only call his deeply human qualities.

The poet Emmett Wheatfall scintillates as well. In 2015, when the memorial was held at Augustana Lutheran Church, he read a piece that three times posed the question, “How on God’s green earth does justice reconcile it?” Six years later, the question not only remains unanswered, but it still also is embedded in Wheatfall’s lines, as a question posed three times to an Oregonian reporter regarding Otis’s execution at the hands of the police.

Wheatfall’s poetry moves and is moving. His reading–a word that does not do justice to his powerful oration–during the memorial connected past and present rife with executions and murders, each “a seismic eruption of injustice.”

Murder comes to Black people in many ways

More so these days, you and I would say

Some of us are executed in our sleep

Others where Black and Brown people pray

Little Black boys like Tamir Rice come to play

Where people of color come to meet

We are murdered on county roads

And on inner city streets

The poem teeters on the edge of despair, referencing Langston Hughes’s “Weary Blues.” But there is little weariness in Wheatfall. His words ultimately expose a constitution that will have no truck with it, that will not allow it to echo in his head. In the end, there are only two things: justice, and the constant demand for it that passes down through the ages.

Anniversaries provide perspective, and perhaps there is no greater surveyor of perspective regarding racial justice in Portland than Dr. Rev. LeRoy Haynes of the Albina Ministerial Alliance Coalition for Justice and Police Reform. To hear him is to hear the voice of the continuum. His words, always humble, remind us that it is not “me” but “we” who make change. His perspective is vast, his Wisdom hard earned. Both reflect an understanding of history and our place in it: the struggle for justice for the brutalities and crimes committed upon Black bodies goes back far beyond Keaton Otis. It reaches past the Civil Rights Movement and Jim Crow, all the way to the tightly packed vessels that carried kidnapped Africans who were enslaved in the Americas.

He seamlessly wrapped up all those fights in this present moment, informing it, guiding it. In his hands, what once must have seemed absolutely impossible to those kidnapped and enslaved Africans, even as they rose up in rebellion, felt within reach. It was a reminder that we stand on the precipice–that we are always on that precipice–of something greater.

“The cry for justice my brothers and sisters on the streets of Portland and throughout this nation will not die until we get police accountability and begin to reimage what policing is for our nation. We have gone too forward to turn around. We must see what the end is going to be. We’ve died too long. We’ve been jailed in prison too long. We’ve been beaten too long. We will continue. We will win this victory. We will transform our nation and policing in our nation.”