Story and photos by Pete Shaw

The second Community Oversight Advisory Board (COAB) town hall took place on May 27 at Portland Community College’s Cascade Campus. While it was a decidedly more sedate and better planned affair than the first town hall held in early April, it once again highlighted significant structural problems with this portion of Portland’s attempt to reign in its police force.

These town hall meetings are part of the Settlement Agreement between the City of Portland, the Portland Police Bureau (PPB), and the Department of Justice (DoJ) stemming from the DoJ’s 2012 report that found the PPB had “engaged in an unconstitutional pattern or practice of excessive force against people with mental illness.” The report also noted “the often tense relationship between PPB and the African American Community.”

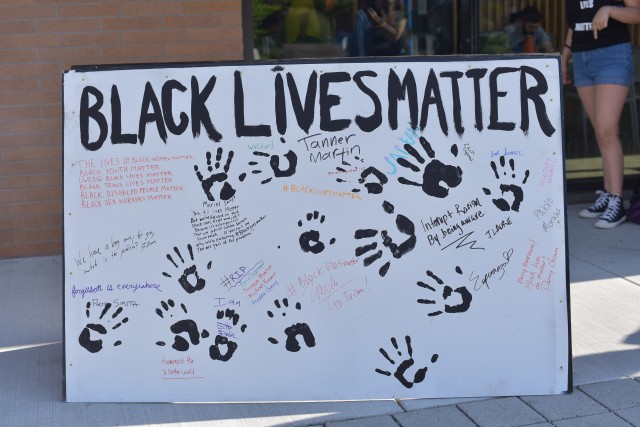

Originally, the DoJ had been asked to examine the PPB’s relationship with communities of color, particularly the Black community in Portland. Though the DoJ investigation of Portland’s police largely glossed over that mission, the public’s response to police violence has predominantly focused on the PPB’s interaction with Portland’s Black community.

The primary purpose of the town hall was to present a draft of the first quarterly report of the Compliance Office and Community Liaison (COCL). The work of the COCL is primarily focused on PPB compliance with the Settlement Agreement, and its quarterly reports are supposed to “provide insights into the activities of the PPB as they relate to the Agreement.” This first report comes just as a Washington Post analysis shows that at least 385 people have been shot and killed by police this year. That amounts to more than two a day.

The meeting began with the introduction of Kathleen Saadat as the new chair of the COAB. Saadat replaces Paul DeMuniz who stepped down due to health concerns. In her introductory remarks, Sadaat stated that she saw her role as making sure “every voice is heard.”

Despite the noble intentions of many of its members, allowing every voice is part of the problem with the COAB, as evidenced at the first town hall. Though it was billed as a forum to “gather input in the form of public and written comments on the Portland Police Bureau’s (PPB) community engagement and outreach efforts,” the PPB was given nearly 80 minutes to present what amounted to an advertisement with no mention whatsoever of the systemic violence at the root of the settlement. According to the COCL’s report “the resources and structures were not in place for the proper planning of this event” and the planning for the meeting “was rushed” which “created confusion and miscommunication as to the purpose and structure of the public hearing.” That blame was laid at the feet of the COAB, a charge many members of the COAB disputed.

The report stated that members of the Portland community found the amount of time handed over to the PPB was “counter-productive to the intent of the hearing.” It went on to state “the amount of time taken and the format which PPB used to present their efforts was perhaps inappropriate for the event.”

The report stated that members of the Portland community found the amount of time handed over to the PPB was “counter-productive to the intent of the hearing.” It went on to state “the amount of time taken and the format which PPB used to present their efforts was perhaps inappropriate for the event.”

“Perhaps inappropriate” is an understatement of immense proportions. Many people at the meeting—including those who have had family members murdered by the police—were not aware the police would be given any time at all. The meeting soon turned ugly, with a handful of people loudly expressing their disgust, and many more showing their disdain in less obvious fashion.

An even larger problem has been the presence of police on the COAB. It is highly problematic that the subject of the DoJ’s report has 5 members on the body meant to craft changes in the PPB. While those 5 PPB employees are advisory only—they are not voting members–their presence guarantees an influence. As Joe Walsh put it in the public comment period, the police “are the defendants in this case. Cops are gangs. They are the baddest gangs in the neighborhood. They don’t answer to no one.”

However, according to the report, some members of the COAB see a threat not from the police, but from some other unnamed-Albina Ministerial Alliance Coalition for Justice and Police Reform (AMA)? Portland Copwatch? Don’t Shoot Portland? Black Lives Matter Portland?– body. “There has also been considerable pressure on COAB members from outside groups to pursue an activist approach to police reform,” wrote the COCL, “versus a collaborative partnership model.”

One question that follows from this is if the COCL believes activism must cease if there are to be changes made to the PPB. It was citizen activism, particularly on the part of the AMA, that resulted in the DoJ’s investigation of the PPB. During the public comment period, Kaylee Luben asked, “Would the COCL prefer passive citizens?” while Dan Handelman of Portland Copwatch said he would continue working “inside and outside” the system to further change. Handelman also urged the COAB to push beyond the Settlement Agreement in making decisions.

Luben also noted that it was the COC–composed of academics from Chicago, Illinois and South Carolin–that was the outsider.

In its report, the COCL recommends that “the PPB and the COAB come together in the spirit of cooperation, collaboration, and mutual respect to systematically address the changes that are needed.” But why should any attempt to reform police, much less hold them accountable or even abolish the current system of policing, involve collaborating with police? During his testimony, Antonio Greeley, President of Portland Community College Don’t Shoot, named just a few of the Black people—Kendra James, Keaton Otis, and Aaron Campbell among them—whose murders at the hands of the PPB makes collaboration seem odd, even perverse. One would think those murders would have forfeited any chance the PPB had in having any input in how it should be reformed.

“Nothing in the Settlement Agreement,” said Handelman, “says the COAB has to collaborate with police. You don’t need to collaborate when people are getting hurt. You can’t risk people to collaborate with their abusers.”

COAB member Jimi Johnson, talking about his belief that the COAB can help build trust between the community and the police stated, “It’s not them versus us or us versus them.” But what is it, then, when the people who are putatively serving and protecting the community are gunning down members of that community and not being held accountable?

The COCL report places a heavy emphasis on the need to restore the legitimacy of the police, sometimes appearing to focus more on changing how people perceive the police rather than on changing the PPB itself. But as Greeley said, the problem is the police, and cleaning up how the public perception will not change anything for those communities who have long been brutalized by police. Prior to Michael Brown’s murder in Ferguson, Missouri last August, police had much greater legitimacy in many people’s minds despite the fact that police, quasi-police, and vigilantes were gunning down Black people once every 28 hours.

That idea of perception over reality can be seen in a section of the report dealing with police training. In referencing the City Auditor’s report released in March–a report the COCL urged be taken with “caution when interpreting some of the results”–the COCL notes how the Auditor reported that PPB officers, on the whole, were not familiar with the PPB’s use of force policy. The COCL posits this unfamiliarity may have been officers reacting to the questioning much like “school students who are unwilling or unable to recite something verbatim on command in a group setting, despite knowing the answer to the question.” Giving police this benefit of the doubt was disputed by some members of the COAB.

That idea of perception over reality can be seen in a section of the report dealing with police training. In referencing the City Auditor’s report released in March–a report the COCL urged be taken with “caution when interpreting some of the results”–the COCL notes how the Auditor reported that PPB officers, on the whole, were not familiar with the PPB’s use of force policy. The COCL posits this unfamiliarity may have been officers reacting to the questioning much like “school students who are unwilling or unable to recite something verbatim on command in a group setting, despite knowing the answer to the question.” Giving police this benefit of the doubt was disputed by some members of the COAB.

Part of the focus on legitimacy and perception includes establishing a database to collect information about police use of force. It is certainly an important step, depending on how that data is used. Yet the fact remains that a police officer can still murder someone and use as an excuse the old saw that he was fearing for his life.

The COCL report also offers alternatives to current policing in Portland. One is to rely less on “aggressive strategies” such as “stops (and searches) that have been shown to be biased by race and ethnicity in other cities.” As well, the COCL recommends that the PPB pursue several community policing strategies:

(1) create monthly beat meetings where officers and community members can interact and solve neighborhood problems; (2) expand PPB initiatives that are consistent with the Respectful Engaged Policing (REP) model, where officers on foot and bicycle patrols have the opportunity to get to know the beat they are serving, have positive encounters with youth, and solve neighborhood problems; and (3) experiment with new models of training that seek to strengthen the officers’ ability to treat people with dignity and respect and prevent interactions from escalating to the point where force is needed.

Historically this is not what police do. The job of police forces as we know them—institutions that in the United States date back to slave days and were used to keep a lid on slave revolts—has always been to reinforce white supremacy by suppressing groups fed up with bearing the brunt of systemic oppression, and who might decide to rise up and try to overthrow the system that weighs down on them.

Achieving these community policing strategies as outlined in the report requires transforming current policing into a liberatory model not based upon protecting and consolidating white supremacy. For starters, real community policing should begin with community members deciding who will police their communities and how that policing will be done. Otherwise the idea of using these and other strategies in an effort to restore trust will only serve to obscure the real purpose of police, resulting at best in slight reforms around the edges, but with no change to the system that has wrought havoc in so many communities.

Another problem that appears to be rearing its head is not separating the acts of individual police officers from the police as an institution. The difference is crucial. Individual officers may be kind, good-hearted people just trying to do the work of serving and protecting in a proper manner; however, they are part of an institution, and certainly feel the demands and pressures from within that framework..

Another problem that appears to be rearing its head is not separating the acts of individual police officers from the police as an institution. The difference is crucial. Individual officers may be kind, good-hearted people just trying to do the work of serving and protecting in a proper manner; however, they are part of an institution, and certainly feel the demands and pressures from within that framework..

Near the end of the meeting, one of the COAB members, Philip Wolfe, signed that he was “learning how to hug” the COAB members who are with the PPB. “They have to put on a face to be a police officer,” said Wolfe, “but they are human underneath.” That is a nice statement, but it is not the point. The DoJ was asked to investigate the PPB because of systemic problems, not the issues of a few individual officers.

When Wolfe finished, COAB member Officer Jakhary Jackson got up from his seat and walked across the stage to hug him. As Jackson walked back to his seat, COAB member Emanuel Price asked for and received a hug from Jackson.

Jackson soon began talking about how he goes out into the community and tries to make good with people, particularly with kids. He lets them know they are not in trouble, that he just wants to talk with them. Jackson said he also invited one of his white colleagues to come out with him and engage people in a congenial manner—if that is possible while wearing a gun and a Taser. Jackson said their interactions have been “cool.”

Cool was probably the last word people who participated in the May Day rally would have used to describe their interactions with the police. In a standoff at the west entrance to the Burnside Bridge, pepper spray was used on protesters. Then, after the rally as people milled about Pioneer Square, police on bicycles and in the vehicle that broadcasts warnings passed by in a manner that appeared antagonistic–going against the flow of traffic—resulting in people coming out into the street and nearly surrounding the announcement truck. The bicycle police doubled back, trying to create a space for the truck to get out, but got stretched too thin. Again, the police used pepper spray. The crowd was certainly unruly, but it posed no danger to the officers.

The truck made its way from the crowd, and then the riot police arrived. Oddly, from the extricated vehicle came the announcement that the rest of the police were trying to leave. Eventually the crowd drove them off, but not before a riot officer shot pepper spray from the back of the riot police truck as it drove off down Yamhill Street. That spray was of malice, not defense. He was in no danger.

Soon, the riot police began firing flash-bang shots. Those close to the action said there was no reason for their discharge. It could be argued that most of the police who were involved in that scene were perhaps little different from Officer Jackson, who, at least at the town hall, fit the bill for the so-called good cop, but that is of little matter when the patterns of institutional abuse are unchanging.

Soon, the riot police began firing flash-bang shots. Those close to the action said there was no reason for their discharge. It could be argued that most of the police who were involved in that scene were perhaps little different from Officer Jackson, who, at least at the town hall, fit the bill for the so-called good cop, but that is of little matter when the patterns of institutional abuse are unchanging.

Certainly, the COAB has a terribly difficult job, and its members are putting in long hours—upward of 20 a week according to many of them–but results so far indicate that many people “aren’t feeling it”, according to COAB member Bud Feuless. Certainly, there were far fewer people than at the first town hall.

In the executive summary of the report, the COCL writes, “The Portland community is thirsty for an organization that is transparent and will provide them with reports on the use of force that will facilitate a more trusting relationship with the police.” That may be so, but Portlanders want a couple of other things even more. They want police to stop murdering people, and they also want justice.

Considering the record of the PPB, and the police system in the US as a whole, it appears that an assessment that has appeared at various police accountability and police abolition events–that the police system is not broken, but rather working exactly as it was designed–holds much truth. If so, justice will require something beyond reform.