Story and photos by Pete Shaw

October 10, 2025

Dear Dad,

I have a movie idea. The setting is Père Lachaise, Paris’s famed necropolis where many artists are buried. In many ways this vast burial ground resembles a city of the living. Its buildings are mostly permanent residences: tombstones, vaults, mausoleums. Some are remarkably elaborate, others elegant in their lack of ostentation. Many are in a state of neglect and irrepair, while others are clearly tended to with loving care.

If the denizens came out at night, what would that be like? Would Frédéric Chopin complain to his neighbor that the view he once had was destroyed by a nearby mausoleum, and so tonight he is debuting his newest work, “Fugue For That Bastard in A Minor”? Maybe he’d go for something more modern, at least for him, and compose a diddy that a perpetually regretless Edith Piaf would sing on her nightly strolls, perhaps joined by Anna Karina and her band of brothers. Antoine-Augustin Parmentier would serve pommes frites to the adoring audience.

But keep an eye out just in case Baron Haussmann is in the area. The guy might begin tearing things down at once and widening the cobblestone avenues. Molière would shout toward him, “Hypocrite!” and command Oscar Wilde to bring him Haussmann’s head on a silver platter. Marcel Marceau would put a finger to his lips and then wag it at Moliere.

Jim Morrison’s neighbors doubtlessly get annoyed that so many people gloss over their resting places while paying respects to him. “Get a load of Mr. Mojo Risin’ over there. You’d think a guy who could do anything would send just one or two visitors over to say, ‘Hello, I love you,’ and maybe even ask for our names.”

They’ve heard this complaint for decades now, and some get cranky. “Oh, let it go already! It does not matter: It is almost dawn, the music’s over, and anyway, no one here gets out alive.”

Estimates range as to the number of people who find their final rest in Père Lachaise. There are about 70,000 burial plots. But when you take into account columbariums and mass graves, anywhere between 300,000 and 3 million people are reportedly buried there, although in most cases 1 million is considered the upper limit. Among them are approximately 166 members of the Paris Commune who after being executed by the French government on May 28, 1871 were put in a mass grave at the foot of the wall where they were lined up and shot, now known as Mur des Fédérés (Communards’ Wall). For two heady months in 1871, after workers and sympathizers decided they’d had enough of not getting their fair share of liberty, equality, and fraternity as it were, tens of thousands of them formed a revolutionary government and seized control of large swathes of the city, effectively saying, “Fuck you, we can do this of ourselves, by ourselves, and for ourselves.” It was remarkably progressive for its time, and it would be so in this time. In the end it was brutally suppressed, another example of the ruling class trying to extinguish the flames of good examples.

Along the exterior of the northern wall of Père Lachaise, on Avenue Gambetta, is the memorial wall Victimes des Révolutions. Created by the French sculptor Paul Moreau-Vauthier and built in 1909, the memorial is composed of some of the stones of the wall against which the Communards stood as they were executed. What first stands out are the numerous pock marks in the stones from the executioners’ bullets, and the figure of a woman standing in front of the wall. She strikes what appears a protective if futile pose, her arms extending from her sides along the wall. Her head is thrown back in despair, or perhaps a desperate, plaintive wail.

Stare a little longer and the stones takes on an ethereal, spectral quality. Behind the woman and along the length of the wall, wispy images of people, some with agonized faces, others holding children, and still more seemingly resigned to their fate, vaguely emerge from the stones. It is meditative and powerful. It is deeply unsettling. It is haunting. And as with the quote from Victor Hugo inscribed in some of the stones in the lower left corner, it cries out for Justice.

A lot of the action of the Paris Commune took place in Belleville, where we stayed. It is probably not where most tourists go when in Paris. Looking online about places to shack up for a few days, there were many comments about it being a place to avoid, similar to ones I read about Marseille. Undergirding these comments, although rarely explicitly said, was that Belleville is a place where migrants live. You know, all the usual tropes: people are too loud, they don’t clean up after themselves, they’re shifty. Taken as a whole, it seemed the comments regarded migrants as definitively not white. No different than among many folks in the US these days. And as with Marseille, the comments would have been comical if they were not so obtuse, so bigoted.

Of course, as with anywhere, there are surely places to avoid at certain times. One of them is not the entrance to Parc Belleville near where we stayed. First, the view is amazing. Belleville is on a hill in the eastern outskirts of Paris, and the park’s apex entrance affords a sweeping vista of much of central Paris, most clearly, the Eiffel Tower. But the real excitement there is the people who gather at dusk and stay for a few hours. They watch soccer matches, make music, talk, sing, read, eat, drink, and dance. They enjoy life, and not at the expense of others. I watched a brief bit of soccer with one guy on his telephone, and it was wonderful sharing a few minutes with someone enjoying The Beautiful Game.

Belleville is not as geared toward tourism as other parts of Paris. I imagine the Michelin starred restaurants, or the ones lacking stars but not reverence among the foodie class, are not found there. I could care less. If the restaurant scene was going to present any problem, it would be in deciding which of the vast variety of available cuisines to sample. We also had at our avail the usual numerous specialized shops–boulangeries, patisseries, fromageries; etc., and there were grocery stores as well. I don’t think I saw a souvenir shop, and finding post cards was a tough Euro. The major tourist areas were elsewhere, many a couple of train rides away from Pyrénées Metro station, just up the street from where we stayed. Which was great, not because I had a desire to see most of those attractions, but because I still love trains.

I do not pretend that I was anything other than a tourist. I assume I reeked of someone from the US, in both good and bad ways, and I bet it took people about two seconds to recognize I was just passing through. And somehow if not, my piss poor French would quickly give me away as my attempts at conversation would not get far before descending to, “Je ne parle pas français. Parlez-vous anglaise, por favour?” But it is nice seeing places from this perspective, and I hope for a few days I was a good neighbor.

Speaking of seeing things from different perspectives, we spent a few hours one afternoon walking some of the old Petite Ceinture rail line. The name means “little belt” and it ran around the far reaches of the city. The Metro brought about its demise, at least for passenger rail, and it closed to most passenger traffic in 1934. By the 1990s, most of the rails were no longer in use (some became part of the regional rail line that runs between Paris and its suburbs, the RER), at least by trains. Some areas were turned by locals into gardens. Others into ad hoc art spaces. Folks without housing lived along some segments. This all was trespassing, access largely gained by climbing over fences or squeezing through holes cut in them. But at least for the gardens and art spaces, it was tolerated. People also illegally walked the tracks, but again this was for the most part ignored by the powers that be.

When we first went to Paris 11 years ago, this was something I wanted to check out. But we never got around to it, largely because it seemed poor form as a guest to break rules so blithely. Now, quite a few chunks of the old line have become City parks. Jessica and I walked a section in the 15th arrondisement in the southwest corner of Paris. A bit of this segment was an el, and it was neat being above the streets, having that point of view. We also walked a portion that like most of the line ran through a trench cut into the earth.

Many of the Petite Ceinture’s old stations are in good shape, including those along parts of the line that remain off limits to the public. And most of them have been converted to other uses. At least one is a concert venue. A couple are dedicated to teaching sustainable environmental practices such as urban farming and upcycling, that is finding uses for items that you might otherwise get rid of. Of course, as this is Paris, it seems food is available in all the upcycled stations, ranging from cafés and bars to restaurants.

I have no doubt those places are fine establishments, but for my and Jessica’s taste, it’s hard to beat the bustling lunch scene in the crypt of the Madeleine Church. At first glance, it might seem unappealing. The eating area is long and narrow, and the seating somewhat cramped. An isolated table for two is not impossible to find, but the tables feel so tightly packed that claustrophobia may as well be on the menu. This is the type of setting that in most cases badly bends my balance, setting the vibrations of most of my nerves to extremely negative.

But this is also part of the charm. Foyer de la Madeleine is advertised as a community restaurant, and the food is made in house by volunteers. The crowd is largely local, or at least it seemed we were the only native English speakers there. The purchase of a meal goes toward getting hot meals to hungry people. The menu changes daily, and you have a couple of choices for appetizer, main plate, and desert, all for 17.5 Euros. The atmosphere is welcoming, and the food is tasty. A wonderful place.

Yesterday was a fine day. We got up early, had a good breakfast, and rode the train to Châtelet station where we transferred to a train that took us to the Latin Quarter. We came out of the Metro at Place Monge and walked down the Rue Monge and soon came to Rue du Cardinal Lemoine. It was a comfortably cool and crisp and sunny Fall morning.

“Which is it?”

“Seventy-four, I think.”

“What does it look like?”

“No idea. But I am sure it is marked.”

It was marked, an otherwise nondescript building with a blue door.

“He lived here when writing The Sun Also Rises. ‘I mistrust all frank and simple people, especially when their stories hold together.’”

“You quote that often.”

“It’s a fine quote. Here’s another great one from him: Never confuse movement with action.”

It was a good morning. We had Fall and we had sunshine and we had Paris. We continued down Rue du Cardinal Lemoine and then turned on to Rue Clovis. Soon we could see the Pantheon and passed by the entrance to Saint-Éienne-du-Mont Church. We turned on to the Rue de la Montagne Sainte-Geneviève and went to the Tram. I ordered a double espresso and Jessica had a latte. It was good, strong coffee, and the day was warming.

“What now?”

“What do you want to do?”

“I don’t know.”

“We could get some food and go to the island.”

I paid the bill, left the tip, and thanked our waiter.

We walked to the market at the intersection of Rue Basse des Carmes, Rue Monge, and Boulevard Saint-Germain. Jessica chose the food. Soon we crossed the Pont au Double to the Île de la Cité. The renovations to Notre-Dame following the fire in 2019 are near completion, and the crowd waiting to get into the cathedral was huge. We walked around it to the Rue de la Colombe and saw the remains of a section of Paris’s first city wall, built around 270 AD. Unlike outside Notre-Dame, the gathered crowd numbered two.

“Where do you find these things?”

“I read a lot. A search on Google for ‘weird shit in Paris’ does wonders.”

We continued north and then walked west along the Seine and passed a man fishing and a couple of groups of tourists admiring the Pont Neuf. Soon we came to the tip of the island. We sat down on a short wall with our legs and feet dangling over the water. Jessica took out the food. The vegetables were crisp, the fruits were juicy, and the sandwiches hearty. It was a good day. We had Fall and we had sunshine and we had Paris and we had lunch. And we had each other.

The bucolic soon gave way to sobriety. As we walked back toward Notre-Dame along the Quai des Orfèvres, we came to the Pont Saint-Michel. I knew the name, but I could not place why. And then it came to me. It was here on October 17, 1961, a few months before Algeria gained its independence from France, that the French national police violently repressed a curfew-violating demonstration by some 30,000 to 40,000 Algerian folks who were also French citizens. The curfew had been declared a couple of weeks earlier by the Paris Prefect of Police, a former Vichy collaborator named Maurice Papon. Keeping with the spirit of a Nazi sympathizing government that deported over 75,000 Jewish people (about 72,500 of them were murdered in either concentration or death camps), Papon’s curfew applied only to the about 150,000 Algerians in Paris and its suburbs. Like the Communards 90 years earlier, the protesting Algerian people were demanding their share of liberté, équalité, et fraternité. The police detained thousands of these protesting Algerian folks, brutalizing many of them, and reportedly under Papon’s orders, they murdered anywhere between 48 (that number provided by a French government commission over 30 years later) to 300 of them. As records are difficult to come by, the number may be higher. Many of these Algerian people’s bodies were dumped into the Seine by the Pont Saint-Michel where they were found floating the next morning.

The French press largely ignored the massacre, and the French government only got around to acknowledging it in 1998. Until the mid-1980s, about the only place one could find an account of it was in the Philadelphia journalist William Gardner Smith‘s 1963 roman à clef, The Stone Face. Indeed, that was where I first heard of it.

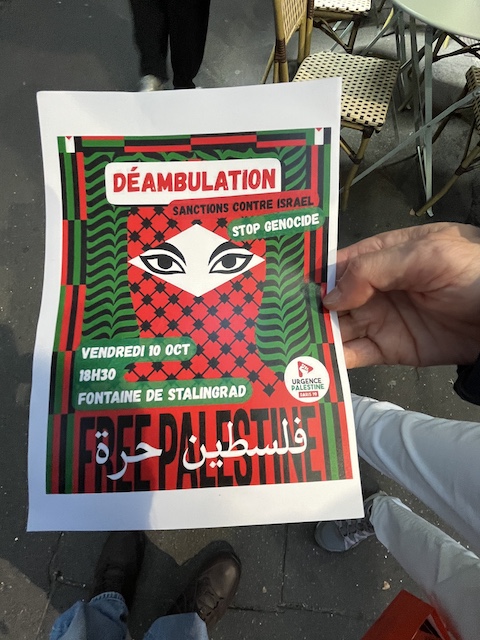

We meandered some more through the Latin Quarter and then the Jardin du Luxembourg. As the sun was setting, we made our way back up to Belleville. Emerging from the Metro station, I saw a march in support of the Palestinian people, demanding an end to Israel‘s genocide of them. It was clear that the best way to pay respect to those Algerian people murdered almost exactly 64 years earlier was to walk in solidarity with another group of oppressed people demanding an end to their colonial torment. It seemed an odd way to wrap up a trip, but it was also Right.

Dad, I imagine when most people think of France, particularly Paris, they think of the Eiffel Tower, Notre-Dame, Sacré-Cœur, or one of many other famed landmarks. That‘s fair. And despite my desire to stray from major tourist sites, when I think of Paris I think of the Louvre. Yet I have never been inside it. But I have gotten great mileage from the story you told me about how when I was 2 or 3 years old, you were sent by the company you worked for to Algeria to do work on the construction of a urea plant. You had a short layover in Paris. Rather than wait for your connecting flight in the airport, you went to the Louvre, hurried through to glimpse the Mona Lisa, and then got back to the airport. In so many ways–the Right ones–it was so you.

We are now over the Atlantic Ocean, headed back to Portland where Friend Tony will pick us up and take us Home. Over three years since you passed, I think about you often. When I read or see something I think you‘d find interesting, I still instinctively reach for the phone. So many times on this trip I wanted to send you a photo or a brief text message. But these days, or at least most of them, that makes me smile.

I Love you.

Love,

Peter