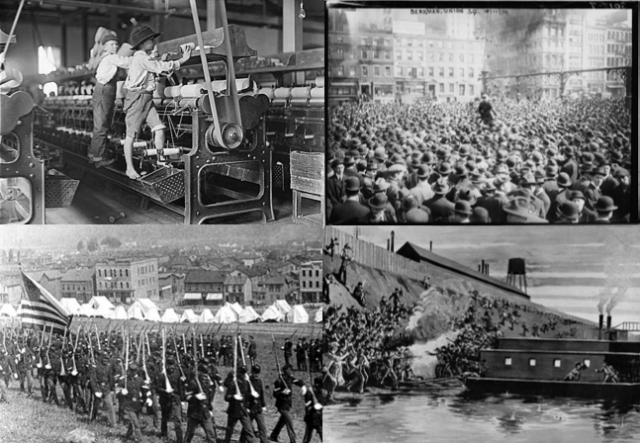

Clockwise from top left: Child labor circa 1923; Alexander Berkman addressing the IWW in Union Square, April 1914; depiction of a confrontation during the 1892 Homestead Strike; State Militia entering Homestead, PA. All images in the public domain.

The Gilded Age is very much in the news.

In early April, President Obama derided a budget proposal favored by Mitt Romney as “thinly veiled Social Darwinism,” referring to ideas usually associated with such men as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller. During his campaign to secure the Republican nomination, Newt Gingrich derided child-labor laws as “truly stupid,” and his suggestion that poor students should be put to work as school janitors was widely understood to be a Gilded Age notion reemerging in our contemporary political debates. In media outlets from Left to Right — including Fox News, the New York Times, and the Nation magazine — the nineteenth century is constantly being cited as a precedent for today’s experience.

With income disparity at a hundred-year high, social-safety legislation under threat, and the economy struggling through one of the worst crises since the Great Depression, it is perhaps not surprising that today’s yesterday of choice has become the Gilded Age, the period in U.S. history from roughly 1877 to 1896 when industrial and urban growth revolutionized American life. Politicians and journalists have suggested repeatedly in the past few months that U.S. society is reenacting a history that occurred more than a century ago. For those on the Right, this is a good thing; for much of the Left, it is a calamity. But so far, neither side has considered the real lessons of an epoch characterized by mass protests and political violence, which at times teetered at the precipice of all-out class war.

Two distinct — though both equally imaginary — visions of the Gilded Age have emerged.

Conservatives — including most Republicans, Tea Party followers, and the commentators on Fox News — have invoked it as a heyday of laissez-faire capitalism, when unfettered competition allowed corporations to maximize profits and efficiency. In their narrative, it was a period when business heroes led the nation to prosperity. “During that time,” Texas Governor Rick Perry wrote, “men like Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Cornelius Vanderbilt … created millions of jobs and massive opportunity for millions more, literally building the infrastructure upon which the world’s greatest economy would grow.”

- Corollary to this story is the denigration of government regulations that followed on the Gilded Age. During the years 1890 to 1920 — a time known to historians as the Progressive Era — reformers, muckraking journalists, and liberal politicians instituted a series of laws and statutes to curb the excesses of capitalism. Anti-Trust acts, pure food and drug restrictions, and workplace safety rules were just some of the ameliorations that arose from these efforts. Since conservatives celebrate the capitalist free-for-all of the Rockefellers and Carnegies, it should be no surprise that the reformist efforts of the Progressive Era draw their ire.

“[W]e let entrepreneurial opportunity be crushed under the weight of the regulatory state,” John Stossel, a Fox News analyst, has written. “The byzantine rules send this message to Americans: Don’t try. Don’t build anything. Don’t innovate. Don’t create anything new.” The Heritage Foundation, a leading conservative think tank, recently issued a report urging Congress to abandon the regulatory instruments that oversee environmental and workplace standards. “[D]o we wish to be governed by the expanding rule of regulation, the rule of administrators who are most certainly not accountable to us?” Glenn Beck, characteristically, has been even blunter. “I hate Woodrow Wilson!” he shouted at a conference for conservatives in 2010.

Liberals, of course, recall the Gilded Age in a very different context. The autocracy of capital, they say, resulted in the repressive subjugation of America’s working families. In their telling, this has become a history of woe and helplessness. Speaking in Kansas this past December, President Obama emphasized the hardships of industrialization, describing children forced to “work ungodly hours in conditions that were unsafe and unsanitary.” Rather than praising the robber barons, he paid homage to another towering figure from a century ago: Theodore Roosevelt. “[H]e busted up monopolies,” said Obama, forcing “companies to compete for consumers with better services and better prices…. He fought to make sure businesses couldn’t profit by exploiting children or selling food or medicine that wasn’t safe.”

These, then, are the two historical visions. The Republicans imagine these years fondly as the heyday of laissez-faire capitalism and tycoon philanthropists. Democrats rue a tragic era when all-powerful bosses inflicted injustices on their helpless workers. Both sides have it wrong. This recollected Gilded Age — a time defined by businessmen and politicians — did not exist.

American workers have never allowed themselves to be either the victims or supplicants of bosses or government. During the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, in particular, they were active manufacturers of their own work lives and politics. Protests were constant — from private contests over workplace control to nationwide strikes that verged at times on open revolt. Powerful labor unions organized walkouts and demonstrations. Socialist candidates were elected to thousands of local and state offices. Radical newspapers and magazines circulated among millions of subscribers.

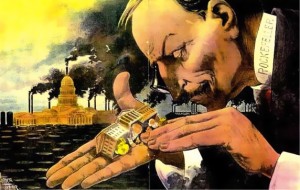

It was in immediate response to this working-class unrest — and the distant threat of revolution — that politicians and business leaders chose reluctantly, tentatively, to relinquish some of their power. They did so not out of the goodness of their hearts, but because of the knife at their throats.

Open warfare between unionized strikers and the forces of state and corporate power erupted periodically between the end of the Civil War and the end of World War One. In mines, mills, railroads, and factories workers and employers confronted one another with guns and bombs, sabotage and assassination. Although the mainstream labor movement usually rejected violent methods, there were always extremists willing to seek vengeance on the oppressors of the poor. As a result, the plutocratic rich were anything but secure during the Gilded Age. Threatened by terrorist retributions, they often lived as prisoners in their own mansions, chaperoned constantly by paid detectives and private police.

“We have supplied over one hundred men to wealthy but timid New Yorkers within the past few months,” the manager of a detective bureau told a reporter in 1893, during a period of radical tension. Two years earlier, an assailant’s dynamite had exploded in the office of railroad tycoon Russell Sage, who survived by shielding himself with the body of his secretary. In Pittsburgh, during the 1892 Homestead Strike, steel executive Henry Clay Frick barely lived through an assassination attempt by the anarchist Alexander Berkman.

By 1900, heads of state had become such frequent targets of radical violence that kings and queens found they could no longer find companies to provide them with life-insurance policies. In 1901, a self-proclaimed anarchist assassinated President McKinley. A decade later, Theodore Roosevelt himself only survived an attempted shooting because the bullet’s impetus was dulled by the manuscript of a speech that he had in his breast pocket.

In 1914, three anarchists were killed when a bomb they had constructed to murder John D. Rockefeller accidentally detonated early, demolishing the East Harlem tenement house where they lived. And in 1920 a car bomb went off in Wall Street, outside the headquarters of the J.P. Morgan corporation, damaging the building and killing dozens of innocent bystanders. “The United States is no place for a man of wealth,” complained a millionaire at the turn of the twentieth century. “The personal danger for every man of wealth has grown greater here every year … the incessant denunciation of wealthy employers is bound to rouse some fanatic in the laboring classes to murder.”

This vicious litany has been effaced from today’s conversations about the nation’s historical experiences. During these years, the United States underwent the bloodiest and most disruptive labor struggle in the history of civilization. That is why some scholars eschew the labels “Gilded Age” and “Progressive Era” entirely, preferring to think of this period as the “Age of Industrial Violence.”

This is the past — not some laissez-faire idyll of happy workers and generous capitalists, but a period of social war with the potential to rend the nation to pieces — that awaits America if the hard-won gains of a century’s activism are finally allowed to lapse.

Thai Jones holds a PhD in U.S. History from Columbia University. His new book, More Powerful Than Dynamite: Radicals, Plutocrats, Progressives, and New York’s Year of Anarchy, is in stores now.

2 comments for “Real Lessons from the Age of Industrial Violence”