Story and photos by Pete Shaw

This does not look good. It is hot at 11 a.m. as I stand under a tree at the Martin Luther King Junior Worker Center, just south of the Interstate 84 overpass. There are about twenty people, all seemingly of Latino descent, awaiting work, nearly all of them with skin darker than the pinkish-white my Irish ancestors handed down to me through the years. With sunglasses and a camera, I should be suspect. I fear I will be all the more when a passerby in a truck shouts an ethnic slur.

A few moments later a man with painter’s garb approaches me, and I ready myself for explaining that however odd, and perhaps dangerous my scene may seem, I am not a threat. But he offers me a mango, a delicious one, and a few moments later, after wiping the juices from my face, I learn the man’s name is Moises. It was a generous gesture, and a tasty one at that.

I am here, and as it turns out Moises is too, for a short jaunt to the Multnomah Building on Hawthorne and Grand which houses the Multnomah County Board of Commissioners. In March, the Board of Commissioners passed a resolution encouraging the use of prosecutorial discretion in response to problems attributed to the Secure Communities Program, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) program that asks local law enforcement detain people without documentation for 48 hours until ICE can determine if they should be held in prison and eventually deported. Those deportations, many of them to people who do have documentation, are occurring at a much faster pace under the nominally liberal Obama Administration than under President Bush. They have torn apart families and made communities less safe as people who fear being detained and deported stop reporting crimes. So the March resolution was a step in the right direction.

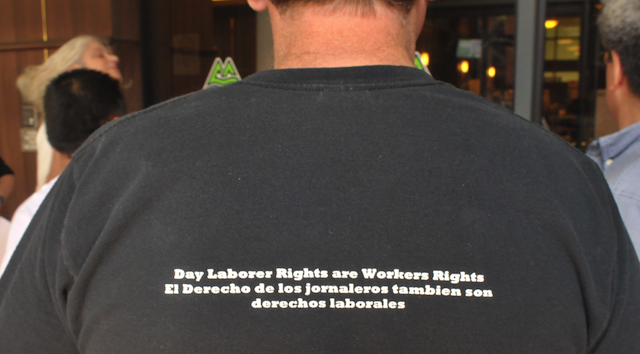

But it was only a resolution, and its legal standing nil, a nicety with no bearing on how people without documentation are treated when arrested by the Portland Police. It was certainly a step forward, but it was not a solution. The purpose of this trip was to get the commissioners to go further and pass ordinance that would, as Romeo Sosa, Executive Director of VOZ, put it, “create a bright line between police and ICE.”

While the corporate media is awash in stories about Arizona’s anti-immigrant SB 1070 and similar laws whose enforcement if not legal wording focuses on Latinos and those who “look like” Latinos, little ink has been spilled about the growing number of local ordinances, and most recently California’s TRUST Act, which rebuke not only unjust deportations, but the anti-American idea inherent to these anti-Immigrant laws that one group of people, namely those with white skin, have a greater right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness than others.

What brings Sosa to the County Commissioners Office is a desire for a Multnomah County law similar to the TRUST Act. “Police have the power to stop anyone who’s suspicious in Arizona. But who is suspicious? Somebody brown? Mexican? Arizona is a testing ground for those laws. We have to prevent those laws. We’d like a bill like California’s TRUST Act, the opposite of Arizona’s law. We want to encourage these laws and make our communities safer. Secure Communities is not secure. It’s fear. People don’t report crimes because they are afraid. Arizona-type laws create a green light to profile, to stop anyone who looks Mexican.”

The introduction to California’s TRUST Act is specific, stating, “This bill would prohibit a law enforcement official, as defined, from detaining an individual on the basis of a United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement hold after that individual becomes eligible for release from criminal custody, unless the local agency adopts a plan that meets certain requirements prior to or after compliance with the immigration hold, and, at the time that the individual becomes eligible for release from criminal custody, certain conditions are met.”

According to Paul Riek, an organizer for VOZ, a “growing tide of communities across the country–counties and states–are setting policies that set their own criteria for when they will honor an ICE hold.” Indeed similar ordinances have been approved in Cook County, Illinois; Santa Clara, California; Washington, DC; and Connecticut. Such legislation, according to Sosa and Margaret Butler of Portland Jobs with Justice, “restricts the circumstances in which local jails exercise immigration detainers, thereby not facilitating the deportation of residents without cause and establishing requirements for federal reimbursement for all the costs associated with immigration detainers.”

Sosa said one of the primary problems with establishing a similar law in Multnomah County, as well as in other communities throughout the county, was that those with the power to craft legislation believe an ICE hold must be honored by local law enforcement. This is false: the hold is optional, and to date, according to the Kathryn O. Greenberg Immigration Justice Clinic of the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, no cities have suffered the wrath of the federal government for not honoring one.

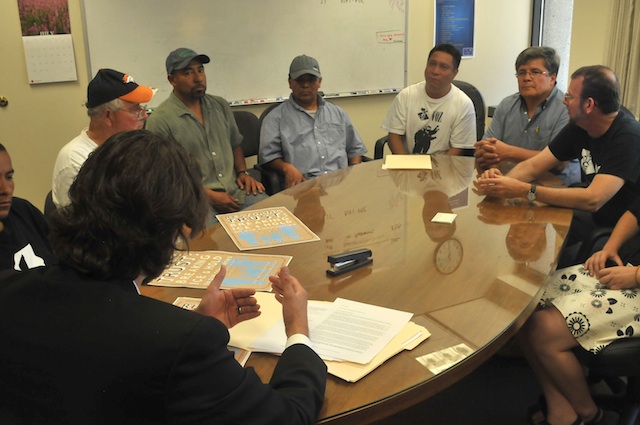

When we arrived at the Multnomah Building, security told us the commissioners’ offices were largely empty, with staff out to lunch or not having time for meetings at the moment. One staff member came downstairs and accepted the information packets Sosa had put together for the commissioners, but he did not have time for an audience. As Sosa and Riek contemplated the next move, Moises told me about his interest in martial arts, and Arabaindia and I struck up a conversation about soccer. A few minutes later Marissa Madrigal, Chief of Staff for County Commission Chair Jeff Cogen, walked through the lobby and kindly took us up to the seventh floor where we sat with her and Guillermo A. Maciel, Policy Advisor for Cogen.

Maciel listened, and responded in Spanish–a respectful, welcoming, and generous act–as some of the day laborers and Sosa explained the importance of crafting legislation that would create that bright line between police and ICE. The meeting lasted about twenty minutes with Maciel saying he would bring the information to Cogen’s attention. Another small but meaningful step forward.

Returning to the Worker Center, we crossed over Burnside where a policeman was writing up a ticket for a driver he had deemed wayward. Passing so obviously as a white man, who despite the protestations of white supremacist types who believe I am the most oppressed entity on the planet, I as usual thought little of the moment. A driver had broken some rule, perhaps according to the letter of the law, or maybe something more or less dependent upon which side of the bed the officer awoke. It was, regardless, a moment little different than when I walk, bike, or drive anywhere.

I asked Sosa what a TRUST Act type ordinance in Multnomah County would mean for those lacking my privilege. His response reminds me of the closing verse of Woody Guthrie’s “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)”, a documentary tune about the death of 28 migrant farmworkers who were being deported from California to Mexico on January 28, 1948. Guthrie wrote the song when he noticed that while coverage of the incident mentioned the names of the flight crew and the security guard, the farmworkers were referred to only as deportees.

The skyplane caught fire over Los Gatos Canyon

A fireball of lighting, it shook all our fields

And who are these friends all scattered like dry leaves?

The radio says, “They are just deportees”

“One thing I have noticed is that these laws produce hate. Now it’s okay to call someone illegal or criminal because she doesn’t have documents.”

This hate, as well as a fear of immigrants, has always been an undercurrent in our nation’s history, but during hard times, such as the current economic recession-depression, that hate and fear is more easily exploited as desperate people seek something tangible to blame instead of examining the capitalism that cyclically produces these downturns. When combined with ignorance, it is a strong mixture. Laws like Arizona’s SB 1070 reflect this desperation, rendering their targets non-people; nameless and faceless, unworthy sub-humans.

And it is that economic system along with its acolytes, producing neoliberal legislation such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), that upends economies such as Mexico’s by, for example, dumping cheap US corn on the Mexican market. Mexican farmers cannot compete with such cheap corn, and many eventually give up farming, often moving to the cities where the glut of labor drives down wages. One of the few alternatives is to go to where there are relatively good paying jobs, in this case, the United States.

“A lot of people don’t know why immigrants are here undocumented,” Sosa tells me. “They ask, ‘Why are they in the US? Why don’t they get in the line for a green card?’ People think you can just get a green card and documents for the right to work here. It’s difficult. There is no line.”

“People want better opportunities for their kids. They want to feed them. I know a man from El Salvador who crossed three borders to get to this country. He told me, ‘They call me a criminal because I want to feed my family. To them, that is who I am. A criminal.’”

“We want to be treated like anyone else. You commit a crime, you should get punished. But not deported.”