Story and photos by Pete Shaw

This Thanksgiving Asbel Sanchez and Susana Garcia will likely not have their husbands. Their children–Asbel and Leonidas; and Yoliana and Victor–will probably not have their fathers. Those absences are because those husbands and fathers have been detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). The situation is not unique. Since President Obama took office, over 1.5 million people have been deported, and they are now deported at a rate of over 1100 a day. That is a lot of torn apart families in a nation that claims to espouse family values.

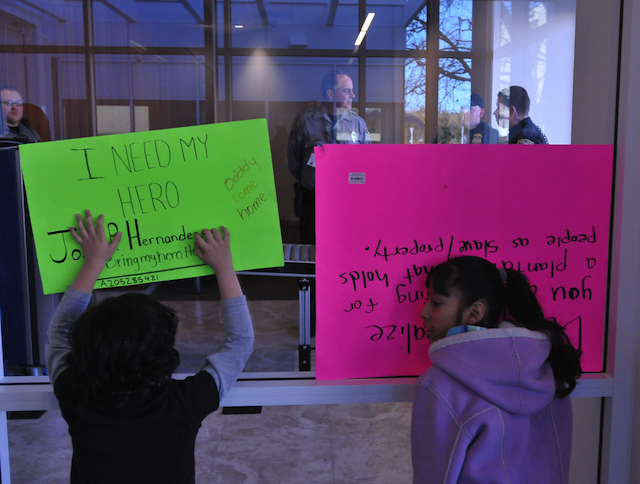

Outside the ICE building on SW Macadam Avenue on the afternoon of November 21st, two members of the Portland police were trying to intimidate Jaime Guzman, an Oregon Dream Activist, into breaking up the rally going on in the lobby. The twenty or so people inside were demanding that their loved ones who have been detained be released so they can be home for Thanksgiving. When it became clear that the officers’ threats were not going to have an effect, one of them asked, “What do you want?” Before Guzman could answer, 6-year-old Leonidas replied, “I want my dad back.”

It was a painfully human moment in a struggle that finds ICE doing its best to dehumanize the people it detains and deports. In one way, this is the essence of the immigrant rights battle. ICE, along with legislators at every level of government in the US, have gone out of their way to depict immigrants, regardless of documentation, as violent criminals and drug dealers. And it is understood that when they speak of immigrants, the image we are supposed to conjure is a person from Central or South America.

Meanwhile, Leonidas speaks for many children whose parents have been detained and deported by ICE. Most of those parents–who are also husbands and wives and sons and daughters, not to mention friends and valued members of their communities–have come to this country in search of that ambiguous term, “a better life”. Very often, they do not come here because they want to, but because they are compelled to. So-called free trade agreements (FTAs) such as NAFTA and CAFTA create huge profits for US corporations by depressing wages, ignoring environmental impacts, and flooding foreign markets with subsidized farm produce that undercuts farmers in those countries.

While the FTAs destroy borders when it comes to flows of capital, labor is still bound by them because human migration laws remain in place, theoretically rendering workers captive by not allowing them legally to follow wages beyond national lines. But people want to work. They want to work for a decent wage. And if they have children, they want to work for a wage that will let them provide for their sons and daughters. Migration to the US is simply a rational economic decision. It is a decision any parent would make–and at great risk. And once here, their labor is again exploited, often under threat of a boss telling ICE that they are here without documentation. Living between a rock and a hard place is a tough dollar.

It is a fair assumption that no parent of any skin color would want to be ripped away from his family, perhaps never to see them again. Whatever ICE and some politicians might like people to believe, this is visceral stuff. This is not being able to put enough food on the table. This is possibly being out on the street. This is not having a mother or father teach you how to throw a baseball or tuck you in at night. This is a gaping hole in people’s lives.

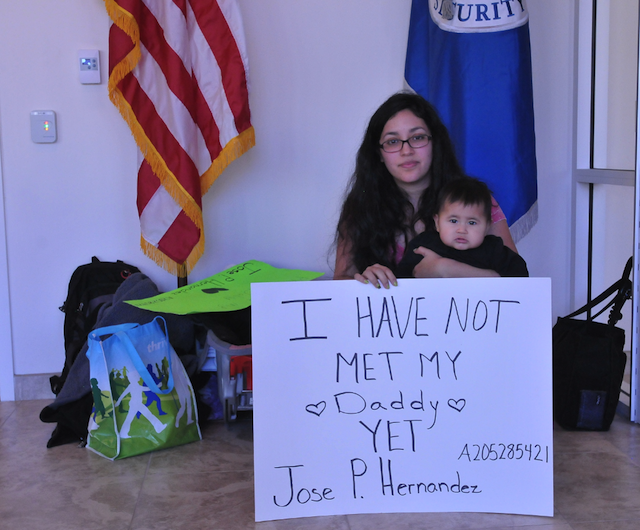

There are two Asbels. The younger is Leonida’s sister. Born in April, she does not know her father. She may never know him. He is Jose Hernandez, and he is currently in the Port Isabel Service Detention Center in Los Fresnos, Texas. Jose has been at Port Isabel for about as long as his daughter, whose smile peering out between two chubby cheeks is the type that drives aspiring doctors into pediatrics, has been alive. He awaits an asylum hearing that will determine if he will stay in the US, united with his family, or be deported. He is there, separated not only from his young daughter and Leonidas, but also his wife, the other Asbel.

“How are you getting by?” I ask Asbel.

“I’m not,” she answers uneasily. “Every day is an emotional, physical, and psychological struggle.”

She and her children live with her mother, Yolanda. Leonidas is home schooled because regular school was proving traumatic. It’s not that he does not get along with other kids–at this rally he is interacting easily with the other young people. But the map of a six-year-old is not so big, and the people who inhabit it are few. There is home, school, maybe some close friends’ houses, and perhaps a store. The people are those close friends, the teacher, siblings, mother, and father. Dads get brought up often, and each time in school proved a painful reminder for Leonidas of his father’s absence.

Home schooling has taken away a trigger, but overarching worries remain. In particular, Asbel says, Leonidas has nightmares that she will be killed or, like her husband, taken away. “I can imagine being a child and not understanding–being in fear that he’s not safe. It’s horrible to see my son cry for his dad, to ask me when he’s going to come, if he’s okay, asking me to pray for his dad.”

When asked how he feels, Leonidas puts his thoughts in the immediate terms of a child his age. “I love my dad so much. My dad, he’s so nice. I had so much fun when he was with me. I love him so much.”

Like Leonidas, 11-year-old Yoliana Garcia misses her father. Six years ago, Yoliana, her three-year-old sister Mariana, and her mother, Susana, were crossing SE 82nd Street at Boyer Road. A car hit them, dragging Mariana, leaving her bloodied body on the side of the road. Yoliana somehow ended up on the other side of the street. The driver kept going. Yoliana’s leg was broken in two places. Mariana did not survive. The last thing she said was, “Mom.”

The police contacted Susana’s husband, Faustino Luis Garcia. They asked him to sign some paperwork. Unbeknownst to Faustino, according to Susana, by signing those papers he agreed not to press charges against the driver. So when Faustino applied for a U Visa, which gives victims of certain crimes temporary legal status, he was denied. What crime? He also applied for political asylum, but again he was denied.

A few months later, Faustino had to deal with an emergency in Mexico. When he came back to the US, he was caught by Immigration. He eventually made it back to Susana, Yoliana, and his son, Victor. But in 2012 ICE raided their home and Faustina was sent to the detention center in Tacoma where he has spent the past year and a half.

Yoliana misses playing games, particularly hide and seek, with her dad. She liked how when he would hide, he was very difficult to find. “Of course,” she adds, “I am a good hider too.”

Susana says when Faustino was deported, for a time Yoliana stopped eating, was sad, and got sick often. And perhaps she also felt some sense of guilt for she often asked her mother if Faustino had left them. Susana explained to Yoliana that some people felt her father was a bad man. Yoliana disputes the charge. “He would never be a bad man. He was always a nice dad. He was always a hard worker. He is always going to be our superhero.”

Obviously Yoliana is biased. But ICE has nothing that disputes her assessment. Faustino has not committed a felony. He is being held, like many people without documentation, because he came to the US in search of better wages to support his family–a search that was a direct result of US foreign policy.

Children are nothing if not resilient. Yoliana has some pain in her leg, and of course, she misses her father. But she smiles easily enough. The other children that took part in the rally also seem like any other children. They laugh a lot, they run around, they shy away from strangers, or they mug for a camera. But the future approaches, and Asbel worries about it. “How are they going to grow up without that parent? What’s going to happen if he (Jose) gets deported and he dies? Is that when there is going to be a change, when a tragedy happens?”

Whether there is a change depends upon many factors. One of the most important of these is presenting immigrants as human beings. The ICE narrative, with its racist overtones, demands that we view immigrants, particularly those without white skin, as a lower form of life, capable only of lawlessness and violence.

Or we can see them as who they are: family members, friends, neighbors, acquaintances, co-workers, fellow bus riders, and all other manner of people who are integrally woven into the fabric of our communities and with whom we interact every day. For that–for the beauty that comes from knowing the people who enrich our lives, even in the smallest way–we should be thankful.

However, they are also people who are being targeted and are terrorized by unjust laws that create insecure communities and destroy peoples’ lives. In being so targeted and terrorized, all our lives are cheapened and morally stained. But people like Asbel Sanchez are fighting back. “Taking a person away from a family is not something I’m going to accept,” says Sanchez. “They have a right to be with their daddy. They have a right to be with their family.”

Sanchez’s words could just as easily be muttered by those of us who are privileged enough not to have to worry about deportation. But words are not enough.

Those of us who have that privilege should use it to take action toward crafting immigration policies that acknowledge historical and political realities and are centered on human rights, not business rights.

And we should be thankful for being able to use our privilege toward achieving a more just world.

For ways you can help fight for immigrant rights, go to the Oregon Dream Activist Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/ORDreamActivist, as well as the home page for the Portland Central America Solidarity Committee at http://www.pcasc.net.