Story by Pete Shaw

Great courage is being show by Black people–particularly young Black women–leading the various groups demanding greater justice and, more specifically, those demanding police accountability and the abolition of the current police system built on a foundation of racism and brutality. Media focus, however, is often on Black men and the problems they face. The lack of Black women’s voices—as well of their unique challenges—is glaring.

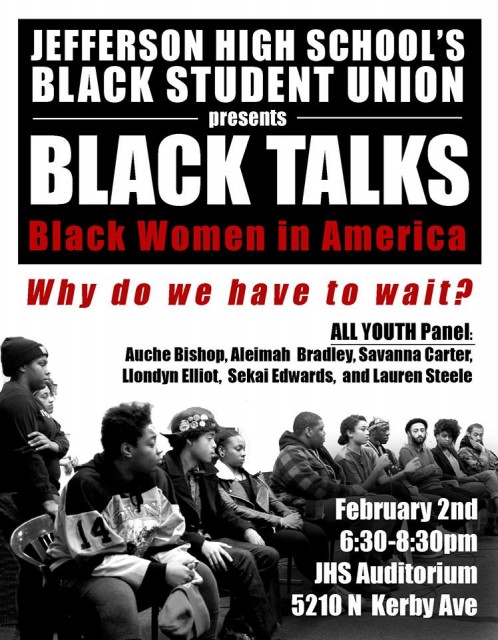

On February 2, the Black Student Union of Jefferson High School held a forum addressing these issues. Titled Black Women in America: Why Do We Have to Wait?, the program featured five students–Aliemah Bradley, Savana Carter, Sekai Edwards, Lauren Steele, and Metropolitan Learning Center student Mykia Hernandez–and covered a wide range of subjects affecting their lives. The result was a series of intimate portraits and extraordinary insights into a world that is either ignored or contemptuously sensationalized in corporate media and sometimes also within the justice groups that many Black women work.

Things took off quickly with a poetry performance by Edwards that set the tone for the evening, which was a demand not only to be heard, but to be listened to. “I spent 14 years talking about your history…I will not be quiet for your convenience,” took on the white, male, straight, Christian narrative that dominates history textbooks as well as popular culture and was also a way for Edwards to nail her own colors to the mast and in so doing strike against any narrative not her own.

Discussion then turned to the issue of how Black women are sexualized and objectified in the United States. Edwards noted how “pop culture demonizes our features but also promotes specific features” such as “big butts and big lips.” “Our bodies are automatically considered sexual,” she said, adding that “the only way you have value as a Black woman…is if you are objectified and sexualized.”

“You got them dick sucking lips,” is a message Carter often hears from men. “My mouth is not on my face to service your genitalia,” she said. “My lips are beautiful, period, whether they service you or not.”

The next question dealt with the appropriation of Black culture. Bradley talked about how offensive she found both its theft and rebranding, noting a recent Chanel fashion exposition in which models wore do-rags, a piece of clothing that has been worn in Black culture for many generations. As often happens with many elements of Black culture that are raided, do-rags were re-designated with the common catch-all “urban.”

Steele followed by saying Black people are the only ones who don’t get credit for their culture, noting that a fashion show incorporating kimonos would be referenced as influenced by and reflecting Japanese culture. Denying the origin of Black culture is something she refers to as “new school blackface.”

“The communities that come up with fashion and music go through so much,” Edwards said. “White people taking it sends the message that we own you. These people come into the communities and reap the benefits without the struggle.”

Bradley said not giving credit to sources was a sign of disrespect. Steele tacked on that such “admiration without any kind of respect” was also a “kind of blackface.”

But as there is this vibrant and creative side to any culture, there is also a dark side reflecting the various oppressions endured by a culture viewed and depicted as inferior by the ruling class and the societal institutions it dominates. Carter noted how part of Black culture is in constant awareness of the reality of white supremacy. “When you’re Black,” added Bradley, “you can’t walk away from it.”

The subject then turned to how light and dark skin perpetuates division of Black women. Hernandez stated that she felt that the concentration on the difference between skin tones—that light skin is better than dark skin–”created a huge divide.” Bradley added that she saw it as “very divide and conquerish.” Taking it outside the Black community, she noted that “in everybody else’s eyes we’re all Black…from the outside we’re all experiencing the same thing.”

The subject then turned to how light and dark skin perpetuates division of Black women. Hernandez stated that she felt that the concentration on the difference between skin tones—that light skin is better than dark skin–”created a huge divide.” Bradley added that she saw it as “very divide and conquerish.” Taking it outside the Black community, she noted that “in everybody else’s eyes we’re all Black…from the outside we’re all experiencing the same thing.”

Edwards disagreed with Bradley’s statement about equal experience, saying that she feels she has more privilege because of her lighter skin. “White people feel more comfortable around me. They think that I have a white parent—they feel more comfortable around me.” In fact, both of Edwards’ parents are Black. She also noted that the argument is nothing new, having its roots in the distinction between house slaves and field slaves.

Steele, whose mother is Black and whose father is white, agreed with Edwards about such privilege, stating that while the “one drop rule still applies,” she was more likely than a darker skinned person to get a job and not be profiled by the police.

Carter followed with the most moving moment of the night. She referred to the “internalized depression” that she feels with being a dark skinned Black woman and told the audience how on social media she has been harassed, being called an ape and a gorilla. She said she often feels insecure about her features, sometimes looking in a mirror and wondering, “Is skin bleach really that damaging?”

“It’s hard to be a lesser beauty,” she said. “It doesn’t feel good. It hurts. And it’s really fucking hard to deal with.”

This young woman, her life out in front of her like a thunderhead, sitting among four other equally brave, strong, and insightful women, was expressing what for a moment sounded like the growing pains of the average teenager, worried about a zit that formed overnight and how this would play out when word got around school. But Carter’s statement carried with it the historical gravity of over 300 years of white supremacy that still weighs down and which no amount of skin cleanser can wash away.

Things then turned to what at first seemed a more jocular subject: hair. For balding men of Irish descent such as this author, hair does not mean much. But hair is part of the body, and it—as well as its lack–is part of identity. The panelists noted how much time they put into getting their hair as they want it, and how that hair becomes a point of identity negotiation. Edwards stated how some of her white friends told her, “You’re hair is not really that Black—it moves.”

The much bigger point of contention surrounding Black women’s hair is that some people feel a compulsion to touch it and will do so without asking for permission. If nothing else, this would seem to breach common manners—and body–but it is the violation of those manners that is all too common. Steele noted how two white women were recently touching her hair at the same time, without her permission. “Hair is sacred in this community. It’s a non-consensual act when you put your hands on my hair.”

“It makes you feel like a walking attraction,” Bradley added.

The women were then asked their views on interracial relationships. Bradley said it is a complicated topic because interracial couples must understand that they are “going to be a public spectacle.” Carter also expressed a tentative interest in how such partnerships would be perceived. “Are we cute together,” she asked “because we’re cute together or because I’m Black and he’s white?”

Edwards and Steele compared the different dynamics between a couple composed of a white woman and a Black man, and one consisting of a Black woman and a white man. “It’s perceived as higher status for a Black man to date a white woman,” said Steele who also noted that white men have had “access to Black women” since slavery, whereas a Black man could be killed for simple looking wrong at a white woman.

Carter along with Steele noted the old saying that you can’t control who you love. Carter added that Black women who date white men are sometimes perceived as trying to get ahead, instead of seen as being in love. “Why does my pride in myself have to be decreased?” she asked. “Why am I sacrificing my Blackness for love?”

The final question of the night dealt with how violence and police brutality affects Black women in the US. Edwards began by noting that most of the conversation about police brutality focuses on young Black men even though women are also in danger. “We don’t talk about women and trans people killed in the street and raped,” mentioning that three transgender women of color were killed in January with little to no mention in the corporate press and were apparently left out of its narrative of the Black Lives Matter movement, giving the impression that only certain Black lives matter.

She also noted how Black women have historically taken major roles in movements, but their work and achievements have been shunted aside in favor of a narrative focusing on men. “People still have the idea that only Martin and Malcolm were in the streets. It’s us who are on the front lines and picketing when Black men are killed.”

Carter breached the subject of sex trafficking stating “I’d rather die than be a victim of sex trafficking.” She described women being beaten and drugged, and then if they escaped from that living torture, they would always have to think about those experiences. “Why is this not acknowledged, these things that happen to Black women,” she wondered. “If you don’t talk about it, it doesn’t exist. And if it doesn’t exist, it didn’t happen.”

Edwards brought the issue of violence home, saying how she had recently seen a girl abused by her boyfriend in the school and nobody took action. “Nobody saw a problem with a girl crying and being choked. It’s hard. It’s become socially acceptable to watch women get beat. We need a culture change.”

And that is the point of the Jefferson High School Black Student Union: to make that culture change. The pamphlet given out at the entrance to the auditorium explained that Black Talks began because of “a lack of space for youth to talk. Although we speak about youth, aim to protect our youth, we don’t let our youth speak. At Jefferson there is an abundance of thoughtful and intelligent minds that needed to to be heard and appreciated in the community. So we took it upon ourselves to create that space.”

During the question and answer session following the panel discussion, panelists were asked how the Black Student Union was received at Jefferson. It seemed the school administration was less than pleased, with Bradley stating that once the union’s members started confronting issues facing Black students, they made administrators uncomfortable and they met resistance.

That resistance has also been found among some students. It seems no group of people fighting to correct past injustice can escape the statement that it should just “get over it,” as if the past does not inform the present and future. But as Edwards asked, “How do you get over the mistreatment of Black people?”

You don’t. You can’t. And you shouldn’t.

But you can work to curtail that injustice in the future and perhaps be part of a chain that creates a world free of it. The Black Lives Matter movement has brought to the fore courageous people who are willing to risk their lives protesting and fighting to change the very police institutions that have resulted in one Black person being killed by police or vigilantes every 28 hours.

However, the movement’s depiction in the corporate press focuses on Black men, with Black women mostly left in the margins. The women speaking at the Black Talks forum were clearly not content to be invisible. They plan to keep speaking out, inviting more people to join the conversation and, as one panelist said when asked to sum up the night’s message in three words, to “end white supremacy”–in particular, the forms of it that oppress Black women.

“There’s a quote that says there’s nothing more powerful than an educated Black man,” said Sekai Edwards. “I don’t think they ever met us.”

The next event held by the Jefferson High School Black Student Union will be The Color of Blackness: Celebrating What it Truly Means to be Black. It will take place at the Jefferson High School auditorium on February 21 at 6:30 PM.